SA9: The Monophony issue

Play one note.

Wait.

Play another note.

Wait.

Play another note.

Stop.

This is an exercise I did for years, building melodies one note at a time with or without regard to harmony or rhythm; letting the shape and flow of the melody define itself based only on the consideration of this question: "Does it work?"

It's an exercise that still causes a certain amount of existential angst. "Does it work?" turns into "what does work mean to me?" turns into "how do our definitions of success compare and contrast?" Each new question becomes the analog to a note in the exercise. I follow the spiral until I find myself curled up in front of the television in need of a nap.

Play a note.

I've found myself using monophonic work as a possible entry level into studying new composers. The desire to tackle the one-note-then-another paradigm has become an automatic point of interest for me as I peruse the record store/library/internet aisles. It has become my roast chicken, well-tied bow tie, or perfectly located fastball. It is my musical equivalent of watching a great artist do something simple in a transcendent way.

Wait.

So, when I decided it was time to do a Sound American issue that would feature a number of writers, beside myself, talking about the music they know and love in terms wholly their own, I naturally gravitated toward what I thought was a musical staple capable of great elegance: monophony. This issue started that simply; what monophonic pieces encapsulate an artist's aesthetic and skill. And, who can speak most eloquently about them?

What lies within is an attempt to answer that question with features by great musicians and writers about great composers and performers: Mark Menzies on Gérard Grisey, Mary Jane Leach on Julius Eastman, Josh Sinton on Steve Lacy, Richard Pinnell on Antoine Beuger, and an interview between Carol Robinson and Tom Johnson.

Play another note.

Regardless of the skill and insight these writers brought to their subject matter, these essays felt like the beginning for this issue of Sound American. There is a specific kind of joy that comes from discovering music. It's a quality that I've tried to portray in every issue of Sound American in one way or another. In these pages, it had been replaced by the joy of understanding music; something that's deep and meaningful in its own right, but needs that spark of spontaneity and unknowing to set it in relief and make it that much stronger. To that end, each essay is paired with the thoughts of a separate musician or artist on hearing the monophonic piece for the first time. It became an interesting exercise to read the interview after the essay; parsing out what is important to different ears and what qualities come to the fore immediately or need immersion to become evident.

Wait.

And, this line of thought opens up other, broader, ideas about what we need or what we think we need in music. Is harmony necessary? What creates motion to our ears? Do we need motion? Is a single voice more powerful than a choir? Obviously, this line of questioning becomes subjective at best, but as I followed one thread after another, one question kept coming back to me: "How do we use limitation?"

Ultimately, the exercise of one-note-then-another is meant to be about limiting yourself to a rational succession of pitches. The endgame of the exercise is a sense of control when given the freedom to do what you want while improvising. But, doesn't the freedom we're striving for in performance have a need for some sort of limitation to ground or define it? As I listened to the pieces for this issue, I found that sense of limitation or ground in different places: obviously in Tom Johnson's Rational Melodies, but also in the cellular structure of Grisey's Prologue and the maniacal sound shaping of Steve Lacy's New Duck. It reminded me of a passage in a Slavoj Žižek essay on F.W.J. Schelling's work on the beginning of temporal thinking;

...our intellectual creativity can be 'set free' only within the confines of some imposed notional framework in which, precisely, we are able to 'move freely' - the lack of this imposed framework is necessarily experienced as an unbearable burden, since it compels us to focus constantly on how to respond to every particular empirical situation in which we find ourselves.1

Play another note.

So, what does that mean for the monophonic composer? Does the lack of harmonic framework present the possibility of moving "freely" for the composer or does it created an "unbearable burden" to be overcome. If the latter, how does the composer climb that particular mountain successfully?

And so, to address that question, Sound American includes an exercise in limitation; in this case, historical context. Issue 9 features four great tenor players of the moment working through the harmonic, rhythmic and historic limitations of Body and Soul, a song heavily defined by Coleman Hawkins's seminal 1939 recording. These saxophonists each dealt with the limitations of a very well known harmony and melody, as well as Hawkins's towering presence in very different and, ultimately, very musically satisfying ways.

Stop.

So, in the end (and after including our return of 5 Questions, this time with Kurt Gottschalk), the issue came about like the one note exercise. It started with monophony, which opened the mind to certain composers and their monophonic works, which further opened into the broader ideas of experience and limitation.

And, this leaves us here. Perhaps in an existential crisis. The narrative string of one note after another has been convoluted by choice as you click from page to page. The availability of information can be paralyzing, ending with you in front of the TV, but I admonish you to stay strong! Start where you want, think of that as your first note, then follow it to what makes sense next, even if it's not on this site, then wait, then move, then wait. When you're done, come back and pick another note.

Nate Wooley-Editor

[1] Žižek, Slavoj. The Indivisible Remainder: On Schelling and Related Matters. London: Verso, 1996

steve lacy

listen to steve lacy's ducks

steve lacy: original new duck

steve lacy: the new duck

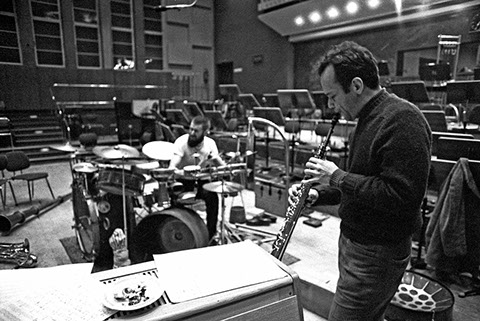

josh sinton on steve lacy's ducks

Swiss Duck, Japanese Duck, The New York Duck, The Duck, Duck, but most often entitled The New Duck. It’s all the same song. It was written and performed by American creative musician and saxophonist Steve Lacy and if his discography is any indication, he performed this song repeatedly (obsessively actually) from 1972 until 1979. I’ve located nine recordings of it from that eight-year window which means he probably performed it dozens of times in that same time frame. About two-thirds of these recordings are solo saxophone recordings, the rest are groups ranging in size from a trio to a quintet. And then all recorded traces of The New Duck disappear until November 2003, seven months before his death from liver cancer. He performed it as part of a solo recital that took place at Rote Fabrik in Switzerland. This was posthumously released as the CD November. I have no idea what brought him back to The New Duck, but I’ve been comparing that final version to his earliest recorded version: a 1972 solo concert in Avignon, France (the earliest recording made of one of his solo concerts) released by Emanem on the album The Weal and The Woe [now released as Avignon and After Vol. 1]. I’ve been comparing these snapshots hoping to glean something about an artistic process that has never made complete sense to me, never sat comfortably with me. And I’ve learned things, but I’m not sure it’s diminished my discomfort. I’ve learned that Lacy’s methods were probably as simple and clear as any musical methods could be. That the sound world he created was deeply indebted to his concomitant profession of being a saxophonist. And that, as much as I might wish for it, Steve Lacy could not be everything I desired in an artist. There were certainly avenues that he did not travel along, but more importantly, he traveled part-way down some avenues and unsympathetically seemed to turn back. For the life of me, I can’t understand why he did not desire more.

For those of you unfamiliar with Lacy, a brief précis is in order. He was born Steven Lackritz to a family of upper-middle-class Russian Jews in 1934 in New York City. At the age of fifteen he became interested in photography. Specifically, he became interested in photographing jazz musicians. Mainly those like Red Allen, Pee Wee Russell and Kid Ory who were playing traditional New Orleans jazz in places like the Stuyvesant Casino. He quickly decided that while he loved photography, he loved the idea of playing this music with these folks even more. He took up clarinet because of his love of Sidney Bechet, which quickly led to playing soprano saxophone as well. By his early twenties he decided that soprano saxophone was the only instrument he wanted to play and not too long after that, he decided that as much as he loved New Orleans music, there had to be something more. By this time he had started attending the concerts of Miles Davis, Charles Mingus and his hero Thelonious Monk. He also started hanging out and playing with musicians like Gil Evans, Cecil Taylor and Sonny Rollins. He was about as ardent a jazz musician as one could be. By the early 1960’s he had started travelling to Europe to play, both with his own groups as well as others and by 1969 he moved permanently to Europe, first to Rome and then to Paris in 1971. It’s at this point that he makes a complete break with jazz’s traditional musical resources. Where he had only played other people’s music up until that time (Monk’s, but also Duke Ellington’s, Mingus’, Herbie Nichols's, Cecil Taylor’s, Ornette Coleman’s and Carla Bley’s), he now played original compositions exclusively. Where he used to play over static harmonic cycles, he composed pieces where the improvised sections were completely free-form. Where he used to play with drummers and bass players providing a steady pulse, he now played in polyphonically arrayed temporal spaces. As far as I know, 1971 is when Steve Lacy’s compositional life begins. It’s an oddly late bloom and odd also for its rigidness. He didn’t begin to perform other people’s music again until the 1980’s (at least not that I’m aware of). From the 1980’s until his death in 2004 he performed a mixture of his music and Thelonious Monk’s with occasional forays into the worlds of Duke Ellington, Herbie Nichols and Mal Waldron. But for the most part he performed his own original compositions; he turned these out at an alarming rate. By the time he passed, his catalog stood at over six-hundred original works. Most have never been recorded.

I met Steve in 2002 when I was finishing up graduate studies at the New England Conservatory. He had left Paris and decided to become a full-time teacher. We met each other at precisely the right time in our lives. We were lucky. I have no clue what if anything Steve learned from me. I learned a lot. Mainly by watching him really closely. And one of the first things he reaffirmed for me was that one can be a professional obsessive and have a fulfilling life. Whatever Steve was interested in, he pursued in a quiet and unwavering way, often for many decades.

For instance, to the end of his life, Steve Lacy was a song man. By that I mean that he always played a song, a song in the traditional jazz sense. Something where you play some pre-composed material followed by some improvising followed by a repetition of the same pre-composed material. When you look at Steve Lacy’s discography (he was fortunate to have been well-documented in his lifetime), what you see is a long list of songs. Usually with one syllable names like The Owl, The Rent, or Moms. And when you listen to these pieces, you never hear free-form improvisations, nor do you hear pieces without improvising. It’s always a mixture of both and almost always in the same exact format: composition-improvisation-composition. It’s maddening and spooky. A little less threatening than Shelley Duval’s reading of Jack Nicholson’s manuscript in The Shining, but only a little.

The New Duck is just such a song. In every recording I’ve heard of it, he played it as he played almost all of his pieces: composition-improvisation-composition. This format held no matter the number of players involved. The compositional part of The New Duck is small. It consists of five to six phrases played in broad, but precise strokes. He plays this twice and then begins an improvisation. The improvisational section is composed almost entirely of unpitched sounds: growls, hard articulations, squeals, multiphonics, mouthpiece sounds (kissing, blowing air) and portamentos. This kind of improvisation was found pretty readily in his work from the late 1960’s and throughout the 1970’s, but then disappeared almost entirely starting in the 1980’s and until his death. I’ll discuss this improvisational method in more depth later in this essay, but for now it’s important to note that The New Duck improvisations represent a unique and uncommon style in Lacy’s already uncommon oeuvre. After he improvises, at a moment of his choosing, Lacy restates the pre-composed melody once and then ends by playing the very first phrase of the composed melody.

Let me take a moment here to explain why I’m so laboriously referring to “pre-composed” parts vs. “improvisations.” It can be argued that the pre-composed parts of Lacy’s songs (the parts transmitted via pen, paper and photocopier) are the actual “song” parts of his compositions. This makes sense since, outside of the realm of academia, it’s just these parts that are thought to be the “meat” of a piece. But part of what was singular about Lacy’s musical world is that no such distinction exists. Lacy’s songs certainly could not exist without his pre-formed thought, but they also could not exist without a spontaneous improvisation dictated by the performer’s circumstances at the moment of performance. I know for a fact that his songs were all of a piece: a little bit of something he had cobbled together beforehand along with something conjured up at that exact moment. I know this because Lacy told me this on numerous occasions (mainly when I was creating a, to him, artificial distinction between composition and improvisation in my playing). Quite simply, a Steve Lacy ‘song’ is a terrifyingly simple structure composed of two processes held in an unchanging relationship: composition-improvisation-composition.

The fixed simplicity of this musical conception is reinforced when you listen to both early and late versions of The New Duck consecutively. Not only are the large-scale structures the same, the improvisations are also eerily similar. Yes, there’s a slight change in details: the ’03 version has more patient phrasing, more varied tempos and the ’72 version is more impassioned and fierce, but essentially Lacy seems to have a fixed game plan. He plays the melody, then he improvises in a highly specific, non-tonal way, then he plays the melody again. The clarity of this plan is reinforced by the fact that after the 1970’s he rarely improvised in this way. That is, from the 1980’s until his death, most of his improvising used fixed, notateable pitches. It was as if the 1970’s were the time when he tried all sorts of experiments with the saxophone and then decided that in the end most of the results were of limited use to him. But over twenty years after he seemed to stop performing The New Duck, when he does return to it, he uses the same exact approach to the improvisation, an approach that he had rarely used for several decades. Lacy seems to have decided that this was the recipe for playing The New Duck: play the melody in an exaggerated fashion, improvise using specific harmonically non-functional sounds and play the melody again. Finally, both these versions share a trait unique to most of Lacy’s music: they’re both fairly quiet. Or at the very least, they’re not screaming exhortations. They’re fairly patient statements that are rarely louder than a forte dynamic. Clearly Lacy was very calm and almost surgical in his use of “noise” when he played this piece.

And yet for all this predictability, I cannot discern any kind of pattern to these improvisations, neither transversely nor intrinsically. It’s very easy to predict when Lacy is going to begin improvising in “The New Duck,” but once he does it’s almost impossible to predict the improvisation’s direction. Since he’s not using pitch sets or a static harmonic rhythm, this stream of information reaches a near-zero level of redundancy. Every sound relates to its neighbors merely by dint of proximity, there’s very little in the way of thematic development or a sense of linear development. In the end, the only common denominator to the improvisations in these two versions of “The New Duck,” is that they were produced by Steve Lacy.

And that impossibly simple, irreducible observation might be an important key in all this.

Lacy-the-composer’s chief muse was Lacy-the-performer, specifically, Lacy-the-soprano-saxophonist. Where other instrumentalists tried to exhibit hidden parts of their musical personality when composing, or to overcome the limitations they’d been saddled with as performers, Steve Lacy grounded his compositions in the research results of his performing life. Whether he was writing for himself, his quintet, his art song trio (with Irene Aebi and Frederic Rzewski) or a chamber orchestra, Lacy’s compositions are audibly indebted to his work as a saxophonist. All of his music is rigorously contrapuntal; the single, indivisible line is foundational to his songs. And the lines are never infinite, they are discrete with clear beginnings, middles and ends, with the pauses determined by the capacity of the performer’s breath (even if the performer is playing a non-wind instrument). Steve Lacy, more than many composers, is a master of the musical punctuation mark. You always know if one of his lines is a statement, question or exclamation. Ellipses are rare creatures in his world. And run-on sentences are almost non-existent. The choice of a song’s pitches was determined by intervals that turned him on as a performer. He would play permutations of small pitch sets over and over again by himself (on piano as well as saxophone) and if he stayed interested (n.b. the litmus test was not if he “enjoyed” himself) he wrote those things down and kept them. So in a sense, the sounds of a Steve Lacy song stand only for themselves and their inter-relationships. They weren’t there to signify anything else; their purpose was to be an idee fixe for the imaginary performer. Lacy wasn’t trying to transcend music or his instrument or any performer’s instrument, he was trying to create objects that situated the performer firmly in the world in which they could enact their daily struggle with the instrument for an audience. Why? Because Lacy loved this struggle, the struggle that all craftspeople have of physically battling with the objects of this world. Steve talked about the physical act of playing music a lot, he studied athletes, but he also studied performing artists as well, the Flying Wallendas, Philippe Petit, Ralph Richardson, Peter Sellers. All people who compelled an audience with the drama they played out by pushing against their physical limitations. Not transcending them, but embodying them.

Steve Lacy didn’t want to overcome the limitations of an instrument because he loved hearing the struggle against those limitations. He extrapolated this to a compositional aesthetic: the sound of limits, of struggle against obvious and simple restrictions and from this was born songs of limited pitch sets, endlessly recurring intervallic patterns, intrinsically human phrase lengths. Steve Lacy’s music isn’t super-human, it’s extra-human; painfully, audibly so. That this was a conscious decision informed by his work as a saxophonist is indicated by one simple fact: Steve Lacy was an excellent piano player. He knew how to write endless melodies that never paused for breath because he cut his teeth on those when he learned how to play piano. But he decided not to write those.

With that embrace of the performer’s physical limits there are upsides: Lacy’s famous patience. It’s a strange thing, because the less people he was playing with, the more notes he played, so I wouldn’t actually call him a spacious player, quite the opposite, loquacious even. But he was patient. There are frequent pauses in his playing, and they’re rarely pregnant or dramatic, they’re pragmatic. Steve had to pause to take a breath and almost no performer I know of was so unruffled by the silences produced by that need for inhalation. One of the biggest obstacles for anyone performing solo on a wind-activated instrument (be it voice, brass, woodwind) is handling the obstinate presence of silence. The silence that surrounds the single utterance will always be there and it can be deeply discomforting because so much of our musical landscape is about the denial of silence’s presence. Every monophonic composer has to face this bogey-man head-on and in Steve Lacy’s case, he simply observed the need for silence as a reality of living in this world, of being a woodwind performer, of being human.

But listening to these two versions of The New Duck ultimately leaves me feeling uneasy. Uneasy because it brings up an unanswerable question: Why didn’t Steve Lacy continue to investigate the formal properties of these more radical sonic findings? Not, “why didn’t he go further?” but rather, “why didn’t he stay out there?” Why did he pull back? Look, in the context of Lacy’s oeuvre, The New Duck is quite abstract, quite radical. In the context of the album The Weal and the Woe it is not (this album has some of his nosiest and most sonically free playing). And in the context of his 1970’s work it’s only mildly radical. But after 1980, this peculiar kind of harmonically non-functional playing that he pioneered disappears. So what happened? What happened to all the experimentation of the 70’s? In this pageant, the ’03 rendition of The New Duck is more like a historical demonstration. As in, “look, here’s an object I made once long ago.” It’s an exotic insect trapped in amber. But the amber wasn’t necessary. The insect was still alive and moving. And if he really did turn his back on this style of playing, why didn’t he do that forever? Returning to The New Duck in the precisely echoically way that he did is terribly sad, sad because it points to a missed opportunity. Lacy had absorbed in a deep and organic way certain fundamentals of our musical culture and in the 1970’s he had started to point to a very interesting, new direction where these fundamentals could lead artist and audience if tweaked only slightly. In essence, he had started gently breaking rules that he had genuinely learned. But he only started. In the end, he seemed to be fine with the rules of musical discourse as they were and he backtracked to a place of notateable pitches, discernible rhythms and concrete phrasing. And to return to the quiet abstractions of the 1970’s with greater patience, hearing and experience like he did in 2003 just makes me unbearably sad. I never realized what I personally wanted Steve Lacy to be until I listened closely to these two recordings. And while I don’t regret the research I’ve undertaken, I did discover some hard truths.

-Josh Sinton

gareth flowers listens to steve lacy

Gareth Flowers is the kind of trumpet player that all trumpet players want to be. He has complete command of his instrument in a way that makes the most difficult of notated passages sound simple, integrated, and just right. His tenure with the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE), along with his solo and freelance work, has made him a quiet hero amongst left-leaning brass players in the city and abroad.

I initially had a hard time finding someone to listen to Steve Lacy, as most of those musicians around me had already had a period of complete absorption in the saxophonist's discography. I took a chance that Gareth, even with his big ears and open mind, had not spent a lot of time with Lacy's music. Plus, his place was on my way home. So, after a short talk about trumpet dork stuff and before tacos, we sat down to experience the 1972 recording of Steve Lacy's The Original New Duck together, both of us for the first time.

Gareth Flowers: Wow…okay! So that was the tune!

Nate Wooley: Yes…that was the tune and, like I said, this was the only track in this process where I was listening for the first time as well. And, that seemed unlike other Lacy things I’ve heard. I mean, that was pretty fucking wild, honestly. Normally it’s kind of this crystalline melodic thing, but…this is your first time hearing Steve Lacy?

GF: I’ve probably heard some before, but this is the first time I knew I was listening to Steve Lacy. I looked in at the timing at 4:50 or something, because he was playing so many short phrases and I couldn’t help but here [Pierre] Boulez.

NW: Yeah?

GF: Yeah, like Oiseaux Exotique. It was one of those things, this is stupid, but I’m hearing bird sounds, and then he plays the tune at the end again it surprised me. You almost forget that there’s a tune.

NW: Because he almost immediately leaves it, which also seems unusual. Typically I think of him spinning the melody out into the improvisation. And, that was such a radical departure from the melody. I can see the Boulez thing. I can definitely hear a bird orientation that’s wilder than Messiaen.

GF: It seems like most of that track is the completely separate voice.

NW: Do you feel like you missed anything by the lack of a harmony instrument or rhythm section?

GF: No. Not at all. I can’t imagine what else I possibly could have wanted to hear alongside that. I was in it the entire time. I didn’t feel like anything was missing or anything.

NW: It’s weird to me. When I started taking on this project one of the things I was interested in was that we’re trained, in a certain way, to think of harmony as one of the main ways that music has forward motion; the dominant-tonic relationship give you some sort of feel…

GF: It gives you movement

NW: Exactly. Every other piece we’ve done has something else that took the place of that motion or movement. But, in this piece, I don’t even know.

GF: I think the shortness of the phrases, especially toward the end of it. There’s almost this feeling of enforced breaths.

NW: And the phrases have gotten shorter and shorter until he gets to the end. I wonder if that’s planned. I always end up wondering that with Lacy. It definitely had that feeling that it was rolling towards the end, which is hard to do.

GF: The commitment on that track is so crazy. I haven’t heard reed biting like that for a while, and the variety. That was like a five minute track and it was all totally remarkable.

NW: It wasn’t screeching for the sake of screeching.

GF: It’s an interesting question, though, that you asked earlier. Do you miss the harmony? For me, I really don’t miss the harmony, but I wonder if it’s because I’m used to listening to solo instrumental pieces and improvisations or whether it’s just because listening to that stuff is just that interesting. It’s just the performer’s imagination coming at you completely.