SA9: The Monophony issue

Play one note.

Wait.

Play another note.

Wait.

Play another note.

Stop.

This is an exercise I did for years, building melodies one note at a time with or without regard to harmony or rhythm; letting the shape and flow of the melody define itself based only on the consideration of this question: "Does it work?"

It's an exercise that still causes a certain amount of existential angst. "Does it work?" turns into "what does work mean to me?" turns into "how do our definitions of success compare and contrast?" Each new question becomes the analog to a note in the exercise. I follow the spiral until I find myself curled up in front of the television in need of a nap.

Play a note.

I've found myself using monophonic work as a possible entry level into studying new composers. The desire to tackle the one-note-then-another paradigm has become an automatic point of interest for me as I peruse the record store/library/internet aisles. It has become my roast chicken, well-tied bow tie, or perfectly located fastball. It is my musical equivalent of watching a great artist do something simple in a transcendent way.

Wait.

So, when I decided it was time to do a Sound American issue that would feature a number of writers, beside myself, talking about the music they know and love in terms wholly their own, I naturally gravitated toward what I thought was a musical staple capable of great elegance: monophony. This issue started that simply; what monophonic pieces encapsulate an artist's aesthetic and skill. And, who can speak most eloquently about them?

What lies within is an attempt to answer that question with features by great musicians and writers about great composers and performers: Mark Menzies on Gérard Grisey, Mary Jane Leach on Julius Eastman, Josh Sinton on Steve Lacy, Richard Pinnell on Antoine Beuger, and an interview between Carol Robinson and Tom Johnson.

Play another note.

Regardless of the skill and insight these writers brought to their subject matter, these essays felt like the beginning for this issue of Sound American. There is a specific kind of joy that comes from discovering music. It's a quality that I've tried to portray in every issue of Sound American in one way or another. In these pages, it had been replaced by the joy of understanding music; something that's deep and meaningful in its own right, but needs that spark of spontaneity and unknowing to set it in relief and make it that much stronger. To that end, each essay is paired with the thoughts of a separate musician or artist on hearing the monophonic piece for the first time. It became an interesting exercise to read the interview after the essay; parsing out what is important to different ears and what qualities come to the fore immediately or need immersion to become evident.

Wait.

And, this line of thought opens up other, broader, ideas about what we need or what we think we need in music. Is harmony necessary? What creates motion to our ears? Do we need motion? Is a single voice more powerful than a choir? Obviously, this line of questioning becomes subjective at best, but as I followed one thread after another, one question kept coming back to me: "How do we use limitation?"

Ultimately, the exercise of one-note-then-another is meant to be about limiting yourself to a rational succession of pitches. The endgame of the exercise is a sense of control when given the freedom to do what you want while improvising. But, doesn't the freedom we're striving for in performance have a need for some sort of limitation to ground or define it? As I listened to the pieces for this issue, I found that sense of limitation or ground in different places: obviously in Tom Johnson's Rational Melodies, but also in the cellular structure of Grisey's Prologue and the maniacal sound shaping of Steve Lacy's New Duck. It reminded me of a passage in a Slavoj Žižek essay on F.W.J. Schelling's work on the beginning of temporal thinking;

...our intellectual creativity can be 'set free' only within the confines of some imposed notional framework in which, precisely, we are able to 'move freely' - the lack of this imposed framework is necessarily experienced as an unbearable burden, since it compels us to focus constantly on how to respond to every particular empirical situation in which we find ourselves.1

Play another note.

So, what does that mean for the monophonic composer? Does the lack of harmonic framework present the possibility of moving "freely" for the composer or does it created an "unbearable burden" to be overcome. If the latter, how does the composer climb that particular mountain successfully?

And so, to address that question, Sound American includes an exercise in limitation; in this case, historical context. Issue 9 features four great tenor players of the moment working through the harmonic, rhythmic and historic limitations of Body and Soul, a song heavily defined by Coleman Hawkins's seminal 1939 recording. These saxophonists each dealt with the limitations of a very well known harmony and melody, as well as Hawkins's towering presence in very different and, ultimately, very musically satisfying ways.

Stop.

So, in the end (and after including our return of 5 Questions, this time with Kurt Gottschalk), the issue came about like the one note exercise. It started with monophony, which opened the mind to certain composers and their monophonic works, which further opened into the broader ideas of experience and limitation.

And, this leaves us here. Perhaps in an existential crisis. The narrative string of one note after another has been convoluted by choice as you click from page to page. The availability of information can be paralyzing, ending with you in front of the TV, but I admonish you to stay strong! Start where you want, think of that as your first note, then follow it to what makes sense next, even if it's not on this site, then wait, then move, then wait. When you're done, come back and pick another note.

Nate Wooley-Editor

[1] Žižek, Slavoj. The Indivisible Remainder: On Schelling and Related Matters. London: Verso, 1996

julius eastman

listen to julius eastman

julius eastman: experimental intermedia excerpt

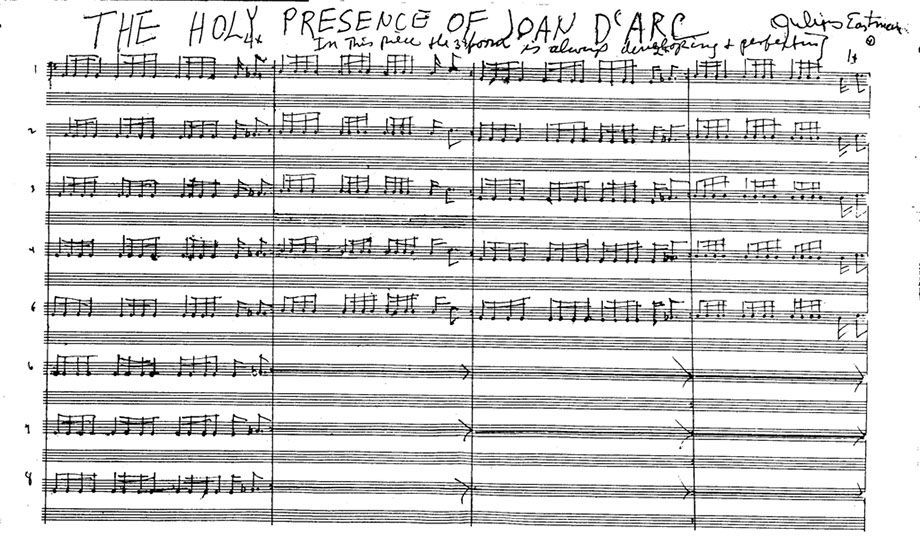

julius eastman: prelude joan d'arc excerpt

Mary Jane Leach on Julius Eastman's Prelude Joan D'Arc

Creating a monophonic composition seems as though it should be easy to do, unless you’re a composer and are aware of the pitfalls that await you. Are you writing to showcase your musical ideas? Writing to showcase a performer? Exploiting an instrument to its extremes? Showcasing its beautiful sound? You can err on the side of simplicity, or complexity. Are you trying to overwhelm or soothe? So many issues, made so much more difficult with that one note at a time restriction.

I will be writing about Julius Eastman’s Prelude to Joan d’Arc (Prelude) for solo voice, which he created and performed, how it relates to his body of work, and showing some of the influences that went into it.

Starting approximately in the 1970s, the composer-performer began to re-emerge (with the exception of composers who were pianists, and who had continued their dual roles), after too many years of separation, and many composers began to write music for themselves to perform. This came about because of music that they wanted to write and/or perform, as well as for expediency. It is much easier to book and pay for a solo concert than one that needs rehearsal time and has to pay other musicians. It also bypasses having to wait for someone else to perform your music.

In his article The Composer as Weakling, Julius Eastman (1940-90) wrote about “the poor relationship between composer and instrumentalist, and the puny state of the contemporary composer in the classical music world. If we make a survey of classical music programming or look at the curriculum and attitudes in our conservatories, we would be led to believe that today’s instrumentalist lacks imagination, scholarship, a modicum of curiosity; or we would be led to believe that music was born in 1700, lived a full life until 1850 at which time music caught an incurable disease and finally died in 1900.” 1

Eastman certainly didn’t lack scholarship, having graduated from the Curtis Institute with a degree in composition. And he most certainly did not lack imagination or curiosity. He was both a composer and a gifted vocalist and pianist. In addition to his own compositions, he performed a wide variety of music. Best known for his performance of Peter Maxwell-Davies' Eight Songs for a Mad King, one of the most demanding vocal parts in twentieth-century music, he also performed music from all periods, from Bach to Haydn to Richard Strauss to [Gian Carlo] Menotti and [Karlheinz] Stockhausen, often under the baton of famous conductors such as Lukas Foss, Pierre Boulez, and Zubin Mehta. He was also familiar with jazz and improvisation, at times performing with his brother Gerry, a bassist with the Count Basie Band, among other groups. His compositions evince the culmination of the wide variety of music that he was exposed to, creating music that is indisputably and uniquely his own.

Writing authoritatively about Eastman is somewhat precarious, as much of his work, both scores and recordings, were lost when he was evicted from his East Village apartment in New York City in 1983 or 84. The sheriff had dumped his possessions onto the street, with Eastman making no effort to recover any of his music. Various friends, upon hearing this, tried to salvage as much as they could, but most was lost. So inferences have to be drawn from the few scores and recordings that do exist, coupled with concert reviews and recollections of people involved in these events, some of which contradict each other.

Eastman’s earliest works, from his Curtis days were primarily for piano, or piano and voice, and had fairly traditional titles (Sonata, Birds Fly Away, I Love the River, Piano Piece I-IV) as well as a few with somewhat provocative titles (Insect Sonata and The Blood). He became a member of the Creative Associates at SUNY Buffalo in 1969, a group of virtuoso performers who performed music by many of the most important living composers. He began to write pieces with an expanded instrumentation, adding electronics at times, and with titles that became more provocative (Touch Him When, Five Gay Songs, Joy Boy).

He moved to New York in 1976 and I have a feeling that, once he left Buffalo, he didn't have access to the same kind of ready group of musicians to perform his work. So, he began to create pieces that he could perform solo, either on piano or as a vocalist. He had two solo concerts in New York that year: one at Environ, Praise God From Whom All Devils Grow, which was reviewed, and another at Experimental Intermedia Foundation, for which there was a recording. Both concerts were improvisational in nature.

In his review of the Environ concert, Tom Johnson noted that “There are probably more composers-performers today than ever before. Many composers have had traditional performing skills, but people like Paganini and Rachmaninoff, whose music really depended on their performance abilities, have been rare….But of course, there are also purely artistic reasons why musicians sometimes prefer to write for themselves instead of for other performers. In some cases composers really seem to find themselves once they begin looking inside their own voices and instruments, and come up with strong personal statements that never quite came through as long as the were creating music for others to play.” He went on to note that Eastman played piano in a “high-energy, free-jazz style,” and sang in a “crazed baritone.” 2 Joseph Horowitz also noted that the singing was “often demonic.” 3 It seems that he usually didn’t combine voice and piano in these concerts, and that his piano playing tended more towards free jazz, while his vocal solos were more minimal and in the style of Avant-Garde classical music.

Listening to his Experimental Intermedia concert, which was primarily solo voice, the singing was fairly ornate and melismatic. At times it even seemed medieval, especially Spanish medieval music, with rhythms being tapped out in that style. Although he had used extended vocal techniques in earlier pieces, such as Macle, written in 1971, this singing is fairly straightforward.

His use of text in the Experimental Intermedia concert, source unknown, is very interesting and reminiscent of Gertrude Stein. For the first 2:20, only four words are sung “To know the difference,” usually in groups of one or two words. Gradually, words are added, usually one at a time, so that by 4:42 sixteen words are being sung in various combinations “To know the difference between the one without another. But he is the one behind the zero. To know the difference between the one and the zero.” By 6:28 twenty-four words are being sung, adding: “Be known to you and to me that the one is after zero and his place is one. His place is behind the zero. His name is one.”

The work of Gertrude Stein was very well known in the circles that Eastman was part of. She wrote in a repetitive style, using a limited vocabulary, as in the example below.

He had been nicely faithful. In being one he was one who had he been one continuing would not have been one continuing being nicely faithful. He was one continuing, he was not continuing to be nicely faithful. In continuing he was being one being the one who was saying good good, excellent but in continuing he was needing that he was believing that he was aspiring to be one continuing to be able to be saying good good, excellent. He had been one saying good good, excellent. He had been that one. 4

Eastman had worked with Petr Kotik in the SEM Ensemble from 1969-75. Kotik wrote Many, Many Women, using text by Stein, and which Eastman performed in at various stages of its development. He also had met and performed with Virgil Thomson, who had written two operas using texts by Stein. And, one of his close collaborators, the choreographer Andrew deGroat, for whom Eastman wrote The Holy Presence of Joan d’Arc (Joan), was a big fan of Stein. Besides having their use of repetition in common, Stein was searching for the “bottom nature” 5 of her characters, while Eastman was searching for “that which is fundamental, that person or thing that attains to a basicness, a fundamentalness.” 6 They were both gay.

Eastman’s Praise God From Whom All Devils Grow concert at Environ, which made a profane interpretation of the hymn Praise God From Whom All Blessings Flow, is his first instance of an overt reference to a religious text, although in a transgressive way. On the other hand, his Experimental Intermedia concert, while it had no overt religious references, juxtaposed super-8 film showing dog shit and close-ups of a drag queen, displaying in your face sexuality and depravity.

By 1978 Eastman, who was black and flamboyantly gay, was composing pieces that were part of a “Nigger” series of works, Nigger Faggot (NF) and Dirty Nigger, both for chamber ensemble, as well as Crazy Nigger, for multiples of one instrument, but usually performed on pianos. It was the first of a trio of pieces usually performed on four pianos. The other two pieces, Evil Nigger and Gay Guerrilla, were written in 1979. Although their titles are provocative, the music isn’t, and they are probably the pieces that sealed Eastman’s reputation as an excellent composer.

So there was this duality going on in Eastman’s work – provocative titles, texts, and multi-media paired with ecstatic music. Gradually actual religious texts began to be used by Eastman, and at least by spring of 1980 he was improvising using religious texts, with titles such as Humanity and the Four Books of Confucious. He was a spiritual person and used texts from many religions.

In 1981 he wrote Joan, scored for ten cellos, that was paired with de Groat’s dance Gravy, which was presented at The Kitchen in New York. It is a vital, through-written, and dense piece full of rhythm and many melodies. Eastman had heard and was inspired by Patti Smith’s Rock N Roll Nigger, and he used that opening rhythm in Joan, using it throughout much of the piece.

In the early 1980s, the Creative Music Foundation received a grant to make three radio programs featuring three composers. Eastman was chosen to be one of these composers, and Joan was recorded at the Third Street Music School Settlement with ten freelance cellists, in a barely rehearsed and quickly recorded session. Steve Cellum was the recording engineer, and he remembers that a couple of weeks after the session, while trying to choose which take to use, Eastman casually mentioned that he wanted to record a vocal introduction, something that hadn’t been mentioned before then. So Cellum lugged his equipment up to Eastman’s tiny East Village apartment, which was not a very good recording situation, but is how Prelude came to be recorded. As far as I know, it was never performed with a live performance of Joan. I had always assumed that it was added in order to fulfill a time requirement for the radio program, but it turns out that there was no such requirement. Also recorded was a spoken introduction, which was the program notes from the Kitchen performance:

Dear Joan,

Find presented a work of art, in your name, full of honor, integrity, and boundless courage. This work of art, like all works of art in your name, can never and will never match your most inspired passion. These works of art are like so many insignificant pebbles at your precious feet. But I offer it none the less. I offer it as a reminder to those who think that they can destroy liberators by acts of treachery, malice, and murder. They forget that the mind has memory. They forget that Good Character is the foundation of all acts. They think that no one sees the corruption of their deeds, and like all organizations (especially governments and religious organizations), they oppress in order to perpetuate themselves. Their methods of oppression are legion, but when they find that their more subtle methods are failing, they resort to murder. Even now in my own country, my own people, my own time, gross oppression and murder still continue. Therefore I take your name and meditate upon it, but not as much as I should.

Dear Joan,

When meditating on your name I am given strength and dedication. Dear Joan I have dedicated myself to the liberation of my own person firstly. I shall emancipate myself from the materialistic dreams of my parents; I shall emancipate myself from the bind of the past and the present; I shall emancipate myself from myself.

Dear Joan,

There is not much more to say except Thank You. And please accept this work of art, The Holy Presence of Joan d'Arc, as a sincere act of love and devotion.

Yours with love,

Julius Eastman

One Dedicated to Emancipation

As verbose as the spoken introduction is, the Prelude is the opposite. It is 11:45, but only uses fifteen words, three of which are only used once.

Saint Michael said

Saint Margaret said

Saint Catherine said

They said

He said

She said

Joan

Speak Boldly

When they question you [used only once]

The three saints mentioned are the ones that Joan of Arc claimed to hear, and who counseled her to speak boldly at her trial for heresy.

Even more minimal than the text is the musical material: consisting almost exclusively of descending notes in a minor chord, a minor rising third, and alternating minor seconds. I was shocked when I realized this, as the piece is so engrossing, that you don’t notice how little is happening musically. There really is no musical development, no compositional sleight of hand, and the words are repetitious. Just plain singing, no extended techniques, no ornamentation. There is the voice, though, and the conviction behind it, the meditation on Joan of Arc, that draws you in. It is probably Eastman’s most minimal work, pared of any excess, and it is ironic that it is paired with Joan, which is probably the most through-written piece of his, and with as dense a texture as Prelude is bare.

Only the first page of the score for Joan exists, which was printed in the program for the Kitchen performances. For many composers of that time, there was a lot of verbal performance practice in effect, with many of a piece’s instructions delivered verbally and not specifically notated in the score, as well as employing a kind of shorthand notation that might have made sense in the context of the moment, but can seem baffling years later. Most of Eastman’s pieces are like this. Joan, though, because it involved so many performers, and usually in situations with little rehearsal time, had to be written out. Eastman had an unforgettable personality, but the cellists that he worked with had so little contact with him that most of them barely remember him, unlike almost everyone else who ever came into contact with him.

Many of us in those days (1970s and 80s) would agree to do a concert, and realize a few days before the concert, that we didn’t have enough material, so it was a not uncommon practice to do a structured improvisation to fill out the concert. Although Eastman didn’t need to stretch out the length of the recording, I envision him using this same process, of preparing for a structured improvisation, before recording Prelude, selecting the text he wanted to use, and an idea of what he wanted to do musically. Usually the tension of performing in front of an audience tightens one’s focus and brings an energy to a performance that cannot be recreated in a rehearsal. That Eastman was able to do so much with so little, in a small, noisy apartment,and with no audience is amazing.

Eastman assimilated many of his wealth of influences, including composers from the past. I cannot know for sure if he was familiar with the operas of Giacomo Meyerbeer, but there are at least a couple of synchronicities between their work. Meyerbeer used the Lutheran hymn A Mighty Fortress is Our God in the overture to Les Huguenots, while Eastman used the hymn in Gay Guerrilla. In Robert le Diable, Meyerbeer has Bertram, a disciple of Satan, singing to the ghosts of sinful nuns. His solo is very similar to the beginning of Prelude, in which Eastman is channeling Joan’s conversations with her three saints – they have the same first three notes, with Betram continuing down to the next note in the chord. Fantasy perhaps, but the musical similarity is striking, and the contrast in characters, saint and sinners, even more so.

Eastman continues in his article on composer/performers:

If we look closely before 1750, we will notice that composer/instrumentalist were one and the same whether employed by the church, the aristocracy, or self-employed (Troubadours).

At the beginning of the age of virtuosity, beginning with the life of Paganini, we see the splitting of the egg into two parts, one part instrumentalist, one composer. At this time we also notice the rise of the solo performer, the ever increasing size of the orchestra, the ascendance of the conductor, and the recedence of the composer from active participation in the musical life of his community, into the role of the unattended queen bee, constantly birthing music in his lonely room, awaiting the knock of an instrumentalist, conductor, or lastly, an older composer who has gained some measure of power. These descending angels would not only have to knock, but would also have to open the door, because the composer had become so weak from his isolated and torpid condition. Finally, the composer would be borne aloft on the back of one of the three descendants, into a life of ecstasy, fame, and fortune.

This being the case, it is the composer’s task to reassert him/herself as an active part of the musical community, because it was the composer who must reestablish himself as a vital part of the musical life of his/her community.

The composer is therefore enjoined to accomplish the following: she must establish himself as a major instrumentalist, he must not wait upon a descending being, and she must become an interpreter, not only of her own music and career, but also the music of her contemporaries, and give a fresh new view of the known and unknown classics.

Today’s composer, because of his problematical historical inheritance, has become totally isolated and self-absorbed. Those composers who have gained some measure of success through isolation and self-absorption will find that outside of the loft door the state of the composer in general and their state in particular is still as ineffectual as ever. The composer must become the total musician, not only a composer. To be only a composer is not enough. 7

Eastman was the embodiment of a composer/performer, one who could construct a dense piece full of counterpoint, such as Joan, and then create Prelude, using so little material that you wonder how it can hold together and work, but through the strength of his performance, he made it work, discovering what was indeed fundamental by discarding the superficial. 8

-Mary Jane Leach

[1] “The Composer as Weakling, Julius Eastman, EAR Magazine, Volume 5, Number 1, April/May 1979, (9th page – pages unnumbered).

[2] “Julius Eastman and Daniel Goode: Composers Become Performers,” Tom Johnson, The Village Voice, October 25, 1976.

[3] “Julius Eastman Sings, Plays Piano at Environ,” Joseph Horowitz, New York Times, October 12, 1976.

[4] A Long Gay Book, Gertrude Stein, p. 23.

[5] Selected Writings, Walter Benjamin, Vol. I, p. 739.

[6] Julius Eastman, in his introduction to his January 1980 concert at Northwestern. Unjust Malaise. New World Records 80638.

[7] “The Composer as Weakling, Julius Eastman, EAR Magazine, Volume 5, Number 1, April/May 1979, (9th page – pages unnumbered).

[8] Paraphrased from Julius Eastman, in his introduction to his January 1980 concert at Northwestern. Unjust Malaise. New World Records 80638.

Composer bojan vuletic listens to julius eastman

Bojan Vuletic has been like a brother to me for the past 10 years. We've shared a lot of musical and non-musical joys and struggles, long conversations and short mental battles. I have performed his music since the day we met and have always found his understanding of the technical mastery of the act of composing to be second only to his desire to represent very real emotional content.

Bojan was in New York to premiere one of his new works: part of his Recomposing Art series, and I used the chance to include someone with a very non-American perspective in the conversation. I consider him a master of the mechanics of thought and emotion. Because of this, I wanted to give him a piece that he would have a hard time placing in a context, so that there would be little historical or technical footing for him to work with. It wasn't until after he'd heard the Prelude that he was given a biography of Julius Eastman.

Nate Wooley: First of all, what’s your general impression? You’ve never heard any Julius Eastman before?

Bojan Vuletic: No.

NW: What are your first thoughts, before I start giving you any information?

BV: Obviously it was clergical in some sense. As there are no instruments accompanying the singing, and it feels like it has some kind of calling it is clear to me that it could be performed in a church. I guess that’s where the musical language comes from.

NW: Do you think that’s why he used monophony?

BV: Yes, that’s apparent, I think.

NW: Now that you’ve seen that he was an African-American composer, I’ll tell you a little bit more about him. He worked mostly in the 1970s. As you noticed from the titles of some of his other pieces, there’s a political element there…some of the titles could be a bit shocking, I guess. With that knowledge, what do you think of the content of the opening. Does it take on a different quality to you?

BV: Of course, yes. If that piece had been sung by a priest, this wouldn’t appeal to me. I think there is definitely some kind of contradiction in the performance. It’s the composer singing right? So, it’s what’s in his head. It’s a little bit over the top from the very first moment; more than you would need to to have your voice be heard in a church, so there’s something to that. And, I think if he composed these other pieces with provocative names, there is probably a political statement.

NW: Did you feel that it was a liturgical sounding piece based on the musical choices and also the fact that he’s invoking the names of saints or by the way he was singing? What part of the way that he sang it played into the way you perceived it?

BV: There was a strangeness before I had any information, because I was actually expecting it to erupt in some ways. And, there were two or three moments where it went somewhere else: one being where he sang the ½ steps.

At the beginning, I thought, “oh, he’ll deconstruct all this”. But, hearing the whole piece I would say…just me, being a non-native speaker,…”St. whatever said”…said in the sense of told [spoke], right?

NW: Yes.

BV: It was like an endless train in a sense, so it could have been St. George said [that] St. Peter said [that], etc. It could be read in that way. But now I think it’s more like whoever is calling, no one is answering (laughs)

NW: Or that he’s not going to reveal what they said.

BV: Well, that could be another thing. In that sense I thought it was; well this is guesswork, but for me when you look at the language of the church, it’s a sort of code. It took a lot of time before the mass was read in the language that the people lived..it was read in Latin, so that was a kind of a code. In this context, that was an association I had. The church is calling you, naming names, but not telling you what it is.

NW: Do you feel like you miss harmony at all in this piece?

BV: No.

NW: What role do you think harmony plays in this composition?

BV: It’s clear he’s suggesting the harmony with the melody, and it’s mostly ostinato figures, so it’s very clear the way it’s structured. There is a thing that he did move sometimes with his voice down a minor second, but not in a completely clear way, so it could either be an intonation thing or it give it a little twist. It has a feeling like a naïve painting approach to me; very clear colors; very simple. But then there’s a twist to it somehow.

NW: But also it seems to me that in naïve painting that there’s a certain kind of expression that comes from the simplicity of it. This is one of the thigns that you’re not getting as part of the project is that this is a prologue to another piece. That pieces is a cello octet that’s more dense.

BV: So the prologue is monophonic and then the piece is dense? That makes sense.

NW: Did you have a different feeling about it when you found out more about him?

BV: For me, the piece didn’t have a connection to what I would think of as African-American musical culture, so it was a surprise to find out he was African-American There were two things that are actually out of a different cultural context, but I had an association with [when listening to this piece]. I had one project called Polyphonie and it was about the hidden treasures that are present, musically, in people from other cultures living in Germany. I did a lot of exploring there and it was pretty interesting. One [of the participants] was a Jewish cantor singing a capella and it sounded nearly like a contemporary piece. Since I didn’t understand what he was saying, I was just looking for musical structures. I could see it had a strong complexity. When I talked to him and figured out what he was doing, I realized it actually had very simply structures behind it. In this context, I find that idea very interesting because [Eastman] is laying out the structure very clearly. So, when you say it’s a prologue to something else, I feel like this becomes the key to what comes after.

NW: I think with Eastman, too, his other music is loosely aligned (in my head at least) with minimalism like Steve Reich/Philip Glass…there’s complexity, but the structure is very clear.

BV: But the big difference between this and a Philip Glass piece is, there seems to be a concert hall attitude to the Glass vocal pieces I’ve heard, which this piece doesn’t have at all. I think if it had that attitude I couldn’t listen to it. I wouldn’t be able to stand it I think. I think it’s very interesting that it’s the composer singing this. I think if it was a repertoire piece for a concert hall, I would hate it probably (laughs)

NW: Well, he’s very heavily classically trained

BV: Yeah, but it’s not obvious, he’s not showing off. It’s funny as well, because I expected this arc, especially with monophonic music I expect a large arc, but he starts very hot and only at the end does he have this deep dynamic fall to almost whispering. It’s a very interesting and strange structure.