SA6: The Maker Issue

Introducing Hal Rammel

Listen to Hal Rammel

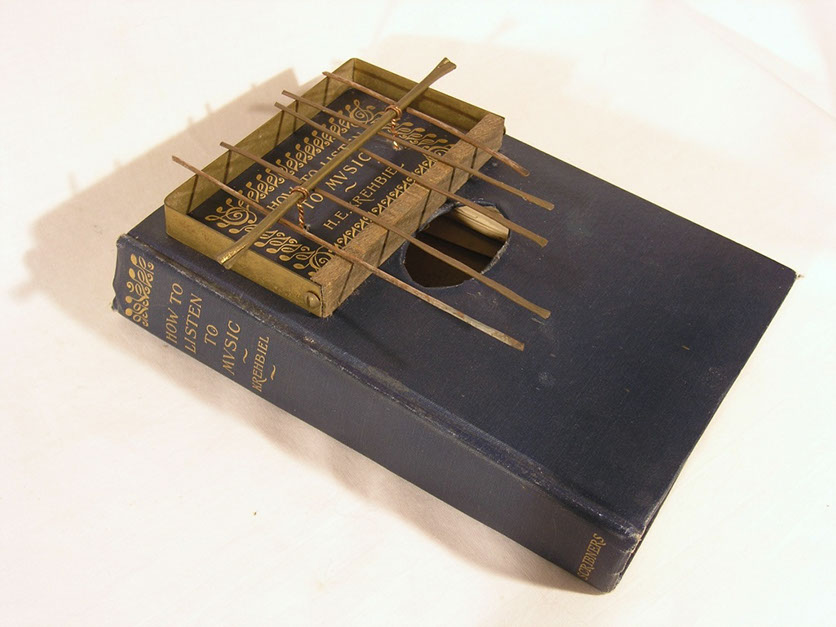

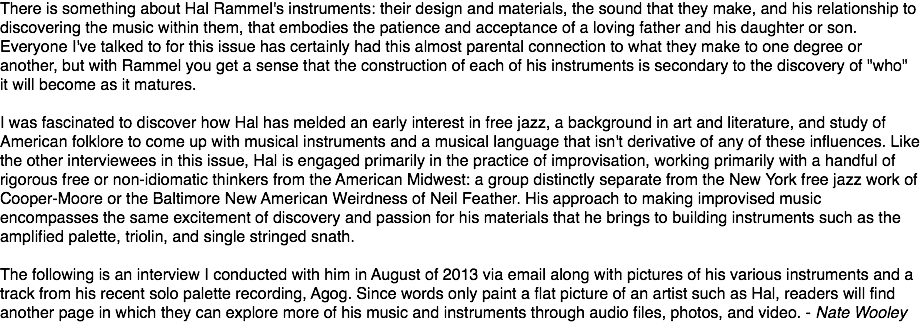

![SOUND AMERICAN: What is your background with music? HAL RAMMEL: In the middle of my high school years I flipped from a strong interest in the sciences to an equally serious interest in literature and music. I started writing, drawing, and listening to music (jazz). I realized very early, fortunately, that I had no talent for fiction or poetry, but I loved drawing. My interest in jazz and, soon after, in modern classical music and music from all over the world, was unstoppable. I had one year of college and left to get a job that would pay the bills leaving me free to work hard on my drawing. I lived in Chicago, working in record and bookstores, and, beyond being a dedicated listener, began to collect African mbira [an African percussion instrument with a wooden resonator and metal keys, often referred to as “thumb piano”]. Within a couple years (we’re up to about 1966 now) I learned about what was happening on Chicago’s southside in Hyde Park [with the AACM or Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians], and started following what Roscoe Mitchell, Malachi Favors, and Joseph Jarman were doing as composers and improvisers. [I] was intrigued with the way their work incorporated unusual instruments. I listened to Harry Partch, Lou Harrison’s early works, and Lucia Dlugoszewski to hear other ways that homebuilt and found instruments could be explored. I have no formal musical training. I just watched and listened and thought hard about what I was witnessing. SA: When did you first start thinking about building your own instruments? HR: My mother was a painter and sculptor; my father, a photojournalist and wood-worker. I grew up going to galleries and museums and figuring out how to make things. My folks were constantly busy with all sorts of projects. When I became serious about drawing, sculpture and other forms were a logical extension. It was all about improvising, so I felt my passion for music could find some active expression by applying those skills to building instruments and figuring out how to play them. And I felt, if I am seriously committed to these instruments, then I have a responsibility to take them out into the world and share my sense of discovery. The first instruments I built were mbira (mid 1970s) and eventually I got up the nerve to show one to Douglas Ewart whose work with bamboo I really admired. He was the only other musical instrument builder I knew and he was very encouraging. From mbira, I moved to a few clumsily built string instruments. I was already playing saw by this time and, again, encouraged by friends (Davey Williams and LaDonna Smith) gained confidence in my ability to improvise. As a public improviser, the string instruments (once I figured out how to make good ones) became an adjunct to my arsenal along with the saw. My musical life as a performer, and improviser and composer, all extends from those early experiences and encouragements. In that light, I also have to credit cellist Russell Thorne who I played with perhaps more than anyone else at that time and whose interests in electro-acoustics led to my development of the palette as an amplified instrument. SA: It sounds like your interest in music came out of being a listener first, as opposed to being grounded in theory and technique on an instrument like piano as a youngster, as most musicians are. Do you think that you would have been drawn to the idea of homebuilt and found instruments if you had had that kind of training? HR: I’ve always taught myself whatever I’ve needed to know whether it was how to build a camera (for pinhole photography), how to draw cartoons, or how to write about American folklore (for the book I wrote on the Big Rock Candy Mountain and other comic utopias in American folk and popular culture). Out of a rebelliousness that I can’t blame on my parents, I always saw school and institutionalized education of any kind as an interference with my personal studies. I had a thorough education in the joys of music as a child: opera from my mother and, from my father, show tunes, standards, and anything that fits into the ‘you name it’ category (going back to a record collection from the 20s which included everything from Bert Williams to ‘Haywire Mac’ McClintock). Neither of my folks played an instrument, but they clearly practiced the ‘go to the library, get some books and figure it out’ school of self-education. That’s how they built the house I grew up in, for example. I really don’t know how formal studies would have affected my musical course, positively or negatively. Perhaps I wouldn’t have had the idea or gumption to bypass any methodical investigation of pitch. I was always inspired by the found. SA: In reading some of your writing, I was surprised to realize what an influence Douglas Ewart was on your building and musical language, since I know him primarily as a saxophonist. Can you give a sketch of the sorts of things he, and other members of the AACM were doing that piqued your interest as a builder? HR: Essentially, Douglas Ewart was the only instrument builder I actually knew. I got to observe his music develop too. He joined Fred Anderson’s band (primarily playing saxophone) around the same time as George Lewis and Hamid Drake. I rarely missed an opportunity to hear that band. I also ran into Douglas selling bamboo flutes at art fairs, so I witnessed the steady elaboration of design and decoration as he learned more and more about his craft, about bamboo and other materials. He was also involved in this creative endeavor in the context of the extraordinary exploration of sound, instrumentation, orchestration, and composition that was happening among his peers in the AACM. These were really inspiring musical experiences. That’s not to diminish what I heard on recordings: Harry Partch’s instruments, Lou Harrison’s percussion music using brake drums and flower pots, the percussion instruments that Lucia Dlugoszewski designed for her compositions for brass, or the eccentric orchestrations I loved in the music of the Memphis Jug Band or Gus Cannon’s records. But I heard the Art Ensemble live many times before they left for Paris. I was able to follow the steady addition of Douglas’s arsenal of flutes all the way through his work with live electronics in the group he had with George Lewis called Quadrisect. Henry Threadgill’s work with the hubcaphone (an expansive array of hubcaps played with mallets) in the trio Air was really impressive. Beyond choosing one hubcap over another, the hubcaphone was found tuning, and played alongside his virtuoso comrades Fred Hopkins and Steve McCall. I heard Henry Threadgill many times bringing various versions of the hubcaphone or hubcawall to concerts by Air. They gave me the courage to try anything and everything that came to mind and to follow wherever those explorations led. All the musicians I have mentioned here have continued to do that to this day. SA: When you were talking about building instruments, I found it interesting that the attitude is one of approaching the instrument on its terms. For those that play, for lack of a better term, "historical" instruments, a lot of this discovery is done by learning the tradition of that instrument. When you approach something you've built, what's the process of discovery like? What's your physical relationship like as you start to work with it? HR: There are so many beautiful instruments in the world that play the world’s most beautiful music in perfect ways. I’m not interested in building yet another instrument that plays that same music as much as I love that music. I don’t mean that in any grandiose fashion. I’m not reinventing music by any means, but for me discoveries come in the interaction of the player and the instrument, not in the newness or unusual quality of the sounds produced. Perhaps I come to this from the point of view of a sculptor or collagist. What is the music within this object? I want the instrument to have as much to say or perhaps more to say about what its music is as I have. And this is a process that can take years. I learn new things about the palette all the time. If I didn’t learn anything new, if I felt I was repeating myself, then it would be time to move on. In the late 70s and 80s, I was seriously interested in single-string instruments. All the mechanical and acoustic issues around mounting a string on a ‘neck’ and positioning it in relation to a resonator sit right before your eyes. When I looked into how to play a single string, there are examples all over the world: the Brazilian berimbau, the endingidi from Uganda, the Japanese ichigenkin, and the diddley bow in the U.S. When I thought about improvising in the pan-idiomatic context of free improvisation all these techniques could be brought into play, not necessarily their idiomatic aspect note-upon-note in the phrasing and rhythm unique to these musical cultures, but in how string sounds are generated and modulated. These approaches might be considered ‘extended technique’ in the Western classical and popular music tradition, but extended techniques were often the building blocks of free improvisation in the late 60s and 70s. Jumping forward to the last decade or so in my work with the amplified palette [Rammel's primary instrument, combining an artist's palette as a resonating board with protruding rods used to manipulate the sound, see photo], I’ve really been inventing how to play this instrument all the way along; even to the extent that I build new palettes that force me to figure out new ways to play them. When I abandoned processing the palette’s signal and decided to focus entirely on building a repertoire of ways to play it (different kinds of bows and mallets, different ways to hold the palette), then my sense of discovery really unfolded.](images/u11517-63.png)

Look At The Instruments

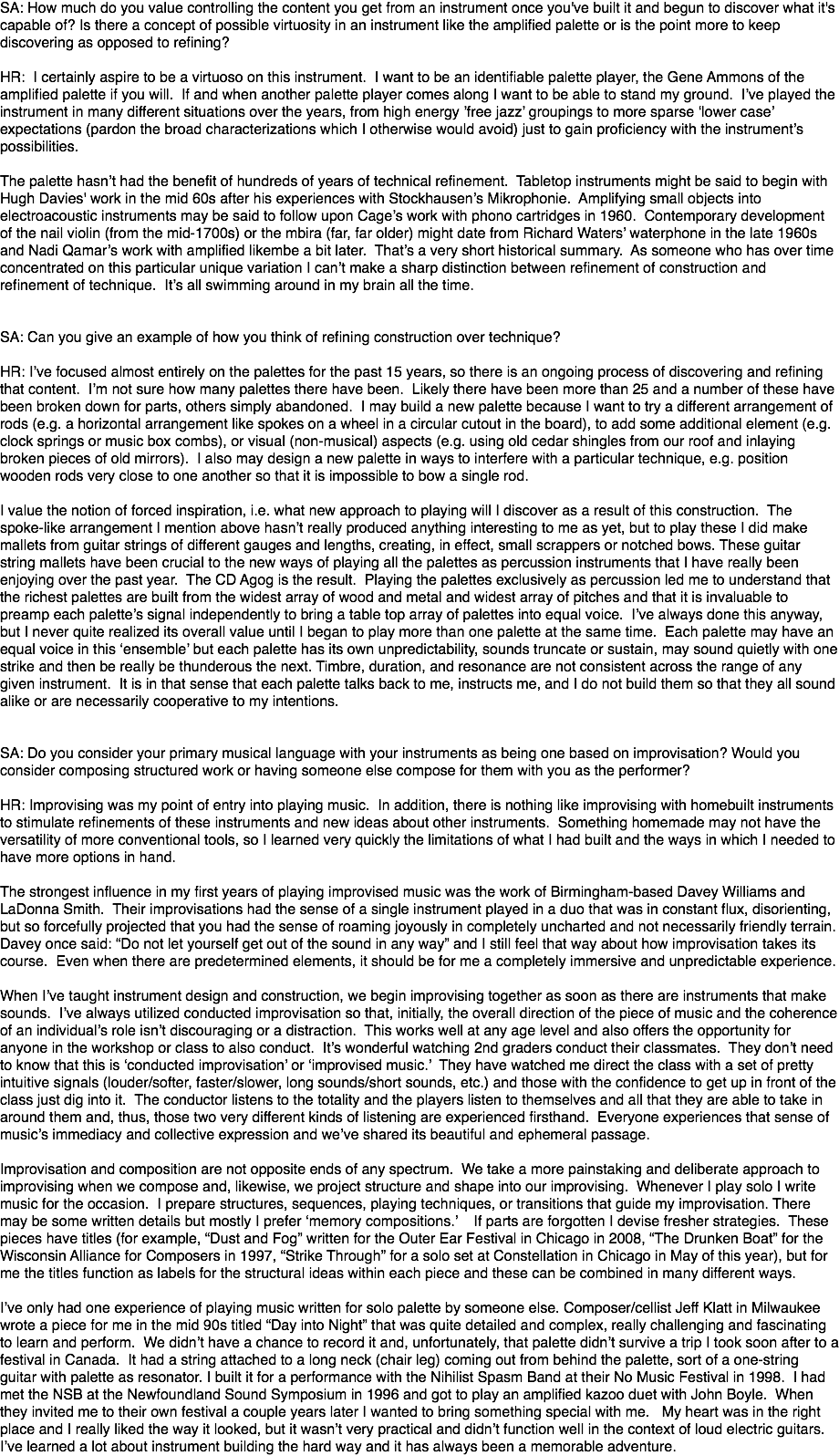

![In so far as I might divide my work between acoustic and electroacoustic instruments and the associated improvising situations, then the single-string instruments (snath and gopychand), the triolin, and the devil’s fiddle might suffice for a catalog of my work as an improvising instrument inventor in that first ‘acoustic’ period. The single-string snath (1985) was the first instrument I made with the structural integrity and versatility for improvisation. I used a scythe handle as the neck. An Old English name for a scythe handle is snathe, so this instrument’s name became snath. These scythe handles have a long eccentric curve and I fashioned a triangular resonator at the lower end with a high bridge so the string could be played like a berimbau with small sticks. I used a slide or stopped the string with my fingers to create a wide variety of percussive string sounds. To explore a variable-tension single-string, I also built and played a large gopychand (ektar) and utilized similar playing techniques but also a violin bow, which can be quite expressive on a slack string. I used these strings quite a bit in the 1990s in the trio Van’s Peppy Syncopators (with John Corbett, prepared guitar, and Terri Kapsalis, violin). The triolin (1986) was what I termed “a nail violin gone awry.” Nail violins date from 1740 and have a discontinuous lineage leading up to Richard Waters’ waterphone in the 1960s. For my first attempt at a nail violin I used thin metal brazing rod (my mother, a metal sculptor, had an unlimited supply) and made a triangular, not circular, resonator that had a handle (chair leg) protruding vertically from the center of the underside. Rotating the triangular instrument in one hand against a bow in the other offered a visual effect I valued over the smooth contour of a circular resonator. The rods are fastened loosely in the soundboard. Some are quite clear and resonant, others lack in sustain or clear pitch and rattle against adjacent rods. I discovered quite quickly that I prefer the randomness and unpredictability of juxtaposed sounds and pitches. Writing about the triolin and these string instruments in the late 80s, I identified my challenge as “wrestling the musicality out of these intransigent objects” and quoted Luis Buñuel: “I believe in intransigence.” [Also] In the late 80s I made several percussion instruments as part of research on an old European form called the Devil’s Fiddle (bumbass, bladder, and string, Teufelsgeige, stump fiddle). I made two of these as part of an article I wrote for Experimental Music Instruments in 1992 and I presented as a paper to the American Musical Instrument Society at their convention in Nashville soon after. The Devil’s Fiddle has one tall vertical pole and a string set up over a resonator to be plucked with a notch bow to create a crude drumroll effect. The pole is also hit against the ground to sound a small pair of cymbals at the top and anything else attached. It’s associated with carnival and street corner music with a history going back hundreds of years. I played these a bit with Van’s Peppy Syncopators but once again it was quite impractical for travel and these now reside in the National Music Museum in Vermillion, South Dakota along with most of my acoustic instruments from this period. Over the years, I’ve constructed many other one-string instruments, several utilizing magnetic pickups. I mounted a flexible bar at the opposite end of the string so I could widely vary the string tension as I played (a string arrangement similar to the Vietnamese dan bau) and I often used an Ebow with these positioning the string halfway between the Ebow and the pickup and, in effect, driving a very slack string. I built 3 or 4 of these single-string electric guitars around this time as they also provided a means of manipulating metal objects over a pickup in the same fashion as various tabletop guitar players. These were my instruments of choice in the trio Raccoons with Jon Mueller, drums, and Chris Rosenau, guitar in the late 1990s in Milwaukee. I’ve built many more instruments than this and not kept very close track of them. When I was teaching actively, I built string, percussion, and wind instruments simply to acquire some hands-on feeling for the elements of their construction. I also built many smaller pieces for specific performances, objects as specific sound sources but not necessarily made to produce a wide range of sounds. There also have been several instruments from the mid 90s that consisted of a finite set of sounds fixed to an amplified frame (e.g. the sistrum and the interocyter), explorations of the idea of an instrument as a musical score in itself (i.e. here are the sounds, choose a duration and method, etc., as a graphic score might present). Instrument building was my way into improvising and improvising was my way to get better at building instruments. I was never interested in creating my own ensemble of unique instruments as the collaborative experience of improvisation with musicians playing more conventional instruments seemed much more likely to stimulate new paths and new music. - Hal Rammel](images/u11575-23.png)

Listen to the Instruments

Hook of a Line, Which Grips (amplified palette - 2013)

Weights and Measures 4 (amplified palette - 2013)

Plink, Plank, and Plunk (snath with John Corbett, guitar - 1995)

Karate (triolin with Van's Peppy Syncopators - 1996)

Watch the Instruments