SA3: The John Cage Issue

John Cage's Song Books

Ne(x)tworks on Cage's Song Books

The BSC on Cage's Song Books

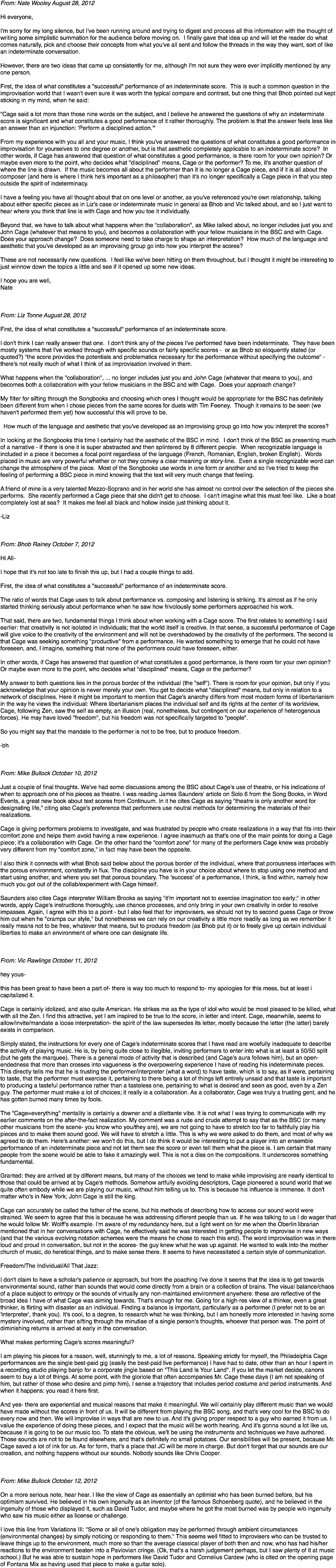

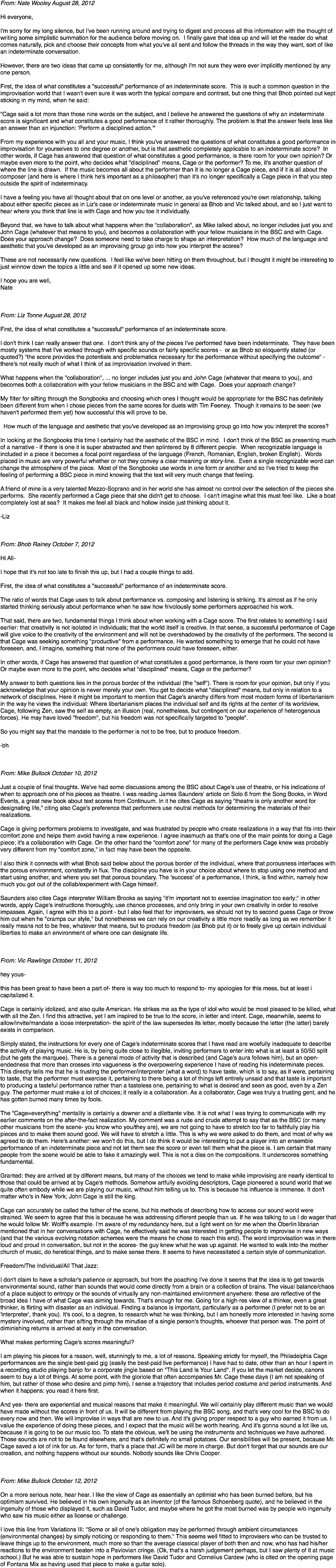

![From: Nate Wooley August 20, 2012 Hey everyone, There is a lot of information here (thanks Vic!) and I've read it now a couple of times. Since no one else has jumped in after Vic, I thought I would take the opportunity to give my impressions and then folks can go from there, or go back to the original question or into a different direction entirely. In Vic's email I latched on to a couple of things. Hegemony and hero worship aside (even though I think these would be interesting topics to follow up and am open to talking about them), if I concentrate specifically on how he's viewing the role of the BSC as performers of Cage and in a "tradition" of modern improvisation, a couple of questions come to mind. This may provide fodder for someone else to expound upon. 1. I'm interested in Vic's statement about the hierarchy of how, when he encounters a piece, he is: "trying to figure out a way that i can play my instruments in a way that remains specific to me and also satisfies the intent of the piece- in that order." In this statement, he’s basically saying that maintaining a very personal musical personality is first and foremost and the intent of the composer seems to come in a far second. Is this a common attitude among you as improvisers? To me, it seems counterintuitive to the basic notion of composition, but with a lot of improvisation language and aesthetic now coming from Helmut Lachenmann, Gerard Grisey, etc. I think a case could be made for this. 2. Let's say we agree with the above idea that, in this musical landscape with improvisers that are much more complex and savvy in the languages they work in the scores of Cage's later period might take on a different meaning than they did when they were being written. If Cage really would be willing to step back and allow you to "just play" (as Christian Wollf did) then performing his works now seems like his work would be nothing more than a group exercise more suited to a rehearsal and discussion amongst players than to a dedicated performance. What then, if anything, makes performing Cage's scores meaningful? Hope everyone is doing well, Nate From: Mike Bullock August 20, 2012 Hey folks, A lot to think about here: About Vic’s quote: "trying to figure out a way that I can play my instruments in a way that remains specific to me and also satisfies the intent of the piece- in that order." In that sense the interpretation of the piece becomes like a cooperation across a gulf of time, where you are kinda "collaborating" with Cage, which I think is a good pragmatic way to approach most indeterminate scores. Morton Feldman gave a nicely distilled version of that with his early scores where the performer is free to choose one element (e.g. pitch or rhythm or duration, but not all of them). There's a hoary old tradition of composers in the "western tradition" fearing or distrusting or even sabotaging their performers, and writing that into their music, e.g. Brian Ferneyhough composing absurdly complex rhythms because he wants the sound of people trying to play them but not quite succeeding. Though Cage is often cited as not liking improvisation, I think he definitely liked to collaborate with his performers. When improvising in an established ensemble, we are all collaborating with each other in a composerly way as well as a performerly way; in a sense, each performance by a long established group like the BSC is like a new iteration of a piece called "the BSC." Not that they all sound the same, but that's an interesting way of thinking about why groups get certain distinct sounds and a distinct level of comfort (not boredom). Vic, I must take exception to your idea that any given BSC piece could be matched to a Cage score after the fact - to me that's falling into the trap of saying that Cage = Everything, that he encompasses all possible sounds and sound-related actions. To the best of my knowledge he never wrote anything that leaves his own input out entirely (in spite of his stated intentions, perhaps). Though the "name that tune" idea is interesting - not that anyone is necessarily going to name the tune, but it would be interesting to hear the guesses of Cage-savvy listeners. And about Nate’s quote: “Maintaining a very personal musical personality is first and foremost and the intent of the composer seems to come in a far second. Is this a common attitude among you as improvisers?” Hard to say, since we don't play a lot of composers' stuff. I'm gonna guess Vic doesn't mean it as a priority thing - like I'm going to throw the score out the window if it starts to bum me out - but just in terms of a to-do list as an interpreter. E.g. never mind all the things that *can* be done with this piece, what makes sense for *me* to do with it? For me, I'm looking at these pieces trying to find an opportunity to do something authentic (eek, that word), that is something that "I would do" or has some kind of vibe with my own values and priorities as a performer, while also looking to be challenged a little by Cage to do something a little new, so I'm not just playing "my thing" and tacking Johnny's name on the end. For example, there's a lot of humor in these scores, some of it subtle, some of it obtuse; I used to do a lot of stuff in my solo work that involved use of theatrical or performative elements, and I took great pains to try to ride a fine line of subtle humor and awkwardness without being dramatic or clownish. So I might be interested in some of Cage's staging instructions, but not the cartoonish or political ones. I'm also not so interested in the pieces that involve, for example, reading Thoreau's face like a score; there was a time in history when doing that was revolutionary and liberating, but now I think that sort of thing is an excellent étude for a student improviser but not so interesting for an experienced one. Cage was not working with people who had already done hundreds of pages of graphic scores in their lives, with maybe some exceptions (Tudor). And, Nate’s other question: 2. Let's say we agree with the above idea that, in this musical landscape with improvisers that are much more complex and savvy in the languages they work in the scores of Cage's later period might take on a different meaning than they did when they were being written. If Cage really would be willing to step back and allow you to "just play" (as Christian Wollf did) then performing his works now seems like his work would be nothing more than a group exercise more suited to a rehearsal and discussion amongst players than to a dedicated performance. What then, if anything, makes performing Cage's scores meaningful? This gets the question of "Is Cage more useful as a philosopher than as a composer?" There are some people who feel this way, and it's understandable - I felt that way for a while when I first read about him. I don't feel that now. With Christian [Wolff], it may have been a situation where, nowadays, he has been playing with experienced improvisers for years at this point and he knew that we fit that category. Maybe he wanted to do that with us because it's a rare opportunity for him to do so at a Conservatory, where most of the students are working on his written pieces (and lucky to be able to wrap their heads around that). Even at New England Conservatory, one of the most forward-thinking conservatories going, anything beyond Mahler is still utterly alien to most of the students and teachers. In order to keep meaning in performing Cage scores, I think it's important to remember that it's not hard to sound like yourself in a Cage score; I feel he wasn't writing to try to get a certain sound out of people, but to set up certain structures and possibilities. -Mike From: Liz Tonne August 20, 2012 Phew! Well here goes..... Certainly, I was being facetious in joking that perhaps I was unknowingly a Cage-ist. I really know very little about John Cage, I have never read any of his writings and the only article I have read about him was in the Gastronomica journal in regard to his work on mushrooms. I suppose what I think I know about John Cage is from hearing other musicians, or people interested in music, or people who once knew him, talk about his work or about him as a person or what ever they think they know about John Cage. Other than that, I have performed 4 of his compositions, some of them more than once. I have also looked long and hard at all 92 of the songs in the Songbooks trying to figure out if and how I could possibly perform any of them. In this light my responses to these thoughts are completely subjective. One of the Cage pieces I have blissfully done a few times now is Ryoan-ji and I could talk about that piece forever because I absolutely love it. The other 3 have all been from the Songbooks, #52 & #53 (the Songbook Aria's) and #85. In the process of selecting pieces from the Songbooks, that I felt I could even begin to pull off, I tried to familiarize myself with a few of the indeterminate scores that could have set the context for the pieces. Because I am a vocalist, and purely out of curiosity, I have also looked at what I think of as Cage's Artsongs, purely notational compositions written for voice and accompaniment. What I have taken away from looking at these scores is that they are all COMPLETELY different and that there is no way to generalize about Cage's music or really have an informed discussion about John Cage's music without selecting which of his vast number of compositional styles and eras you are talking about. Even within the Songbooks themselves the diversity of approach is immense. They range from fluxus-like theatre pieces to traditionally notated scores. So, as improvisers perhaps we need to specify that we are talking about how John Cage composed to accommodate improvisation? But even here we are in a vast sea of many, many different improvisational systems. Many, I'd even begin to say most, of these seem highly specific - not much Free Jamm allowed. Let's say we agree with the above idea that, in this musical landscape with improvisors that are much more complex and savvy in the languages they work in the scores of Cage's later period might take on a different meaning than they did when they were being written. I definitely did not feel in the least bit savvy trying to sing the Arias - I carefully selected techniques which I felt I had developed for myself and applied them to the system detailed in the directions to the score. Basically, I was trying to make it workable for me with the tools which my personal experience has given me - and it was still very, very challenging. I found these to be serious compositions and I have gained a lot of respect for each and every one of them as a separate entity. "Is Cage more useful as a philosopher than as a composer?" No. For me, I'm looking at these pieces trying to find an opportunity to do something authentic (eek, that word), that is something that "I would do" or has some kind of vibe with my own values and priorities as a performer, while also looking to be challenged a little by Cage to do something a little new, so I'm not just playing "my thing" and tacking Johnny's name on the end. That pretty much sums it up for me too. I'm also not so interested in the pieces that involve, for example, reading Thoreau's face like a score; there was a time in history when doing that was revolutionary and liberating, but now I think that sort of thing is an excellent étude for a student improviser but not so interesting for an experienced one. Interesting point Mike - many of these don't readily lend themselves to personal expression, but they are compositions! They aren't meant to be about the performers - though some allow a lot of freedom to put yourself in there. (and some... Ryoan-ji.....are transcendent) Thankfully that is all I can think of to say right now. liz From: Mike Bullock August 21, 2012 This is great, Liz - coming from the one among us who has most likely played Cage the most. Re: your last comment relating to personal expression - last night in conversation with Linda and Vic and Liz W, I was reminded of a major revelation Cage had in his early career (when he was writing some of these art songs you are talking about, I think, like The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs). He was trying to pour a lot of himself into his pieces, and people were just "not getting it" and finally he had the revelation "music may be expression, but it's not self-expression." I thought that was a great way to sum up moving beyond the personal into the trans-personal, interdependent way of making music that is a lynchpin of improvised music. -Mike From: Bhob Rainey August 23, 2012 Hi, I'd like to take a step back and try to address some of the fundamental questions that Nate is putting forth and that always seem to be looming whenever an improviser from our generation performs an indeterminate score. Implying that contemporary improvisers have internalized and possibly improved upon both Cage-ean concepts and the instrumental language that arose around those concepts, Nate asks, "What then, if anything, makes performing Cage's scores meaningful?" Meanwhile, Vic postulates that, to a listener, an improvised performance could be indistinguishable from the performance of a Cage score. I think that the trouble expressed by both of you boils down to the question, "What constitutes a good performance of an indeterminate piece?", and, for the improviser / performer, "Where do I place my disciplined effort?" As to the first question, it's obvious but not always expressed that there is a significant shift in the score / performance relationship with indeterminacy. It is possible with a work by, say, Brahms, to derive the score from a given performance – just by listening you can figure out the notes, rhythms, dynamics, etc. So, the performance is a "realization" of the score, and the two resemble each other. The degree to which the performance resembles the score is a major criteria for judging the quality of the performance. This criteria is absent in indeterminacy, where a single score can produce radically different performances, none of which reveal with any kind of accuracy the score underlying them. In this case, the performance is an "actualization" of the score; there is no resemblance, but there is still an intimate link – the score provides the potentials and problematics necessary for the performance without specifying the outcome.* The lack of resemblance between performance and score in indeterminate music opens up a wide field for charlatanry – no one can tell if you're playing it "right" or not, so why not do whatever you want? Cage already supplied the answer: "Permission granted. But not to do whatever you want." Depending on your disposition, this is either a perfectly succinct summation of a fascinating worldview or it's a coy dodging of the question. Cage said a lot more than those nine words on the subject, and I believe he answered the questions of why an indeterminate score is significant and what constitutes a good performance of it rather thoroughly. The problem is that the answer feels less like an answer than an injunction: "Perform a disciplined action." Think of it like this: a score like Song Books is a framework for an event. "We are gathered here this evening for a performance of Song Books." Song Books is the reason for the gathering, and it provides a number of significant potentials for the direction of the evening. It opens up possibilities but also closes many others. It tells you what to do, but not so specifically that you forget the other parts of the sentence: "We are gathered here…" "We" are the performers, audience, animals, the things in the space of "here", which is both place and time. We are spending a certain duration living around Song Books, and our respect, our disciplined effort, is directed towards that ecosystem. It isn't "Song Books will be performed this evening" or "I'm playing Song Books tonight" or "This is what Song Books sounds like". A good performance of Song Books is a productive, ethical engagement with the score, the time, the place, and the life of the performance. You could say, "remove the 'score' part and you have improvisation". I would say that the "score" in improvisation (as we practice it) is an embodied, fluid history. It is always unfinished, almost impossible to prepare. The advantage of an indeterminate score is that you can know better what you are preparing and can proceed with the confidence that this preparation has been in some sense sanctioned by a thoughtful person (i.e., the composer). The freedom that emerges is really a freedom from your own taste (quite different from the freedom to do whatever you want), so that you might open up a space for beauty rather than fill a space with your ideas. Can you do the same thing with improvisation? Yes, but it's hard. You have a more direct conflict with your own history, your taste, and as soon as you feel that you've surpassed these things, they adapt. I love the self-splitting snags of this particular struggle, but these are not the only things I love about making music. I'm tired now. -bhob * And if you haven't read Joe Panzner's dissertation on Deleuze and Cage (to which I am somewhat indebted for my Deleuzian interpretation of the relationship between scores and performance), you're really missing out.](images/u10766-198.png)

SA3: The John Cage Issue

John Cage's Song Books

Ne(x)tworks on Cage's Song Books

The BSC on Cage's Song Books

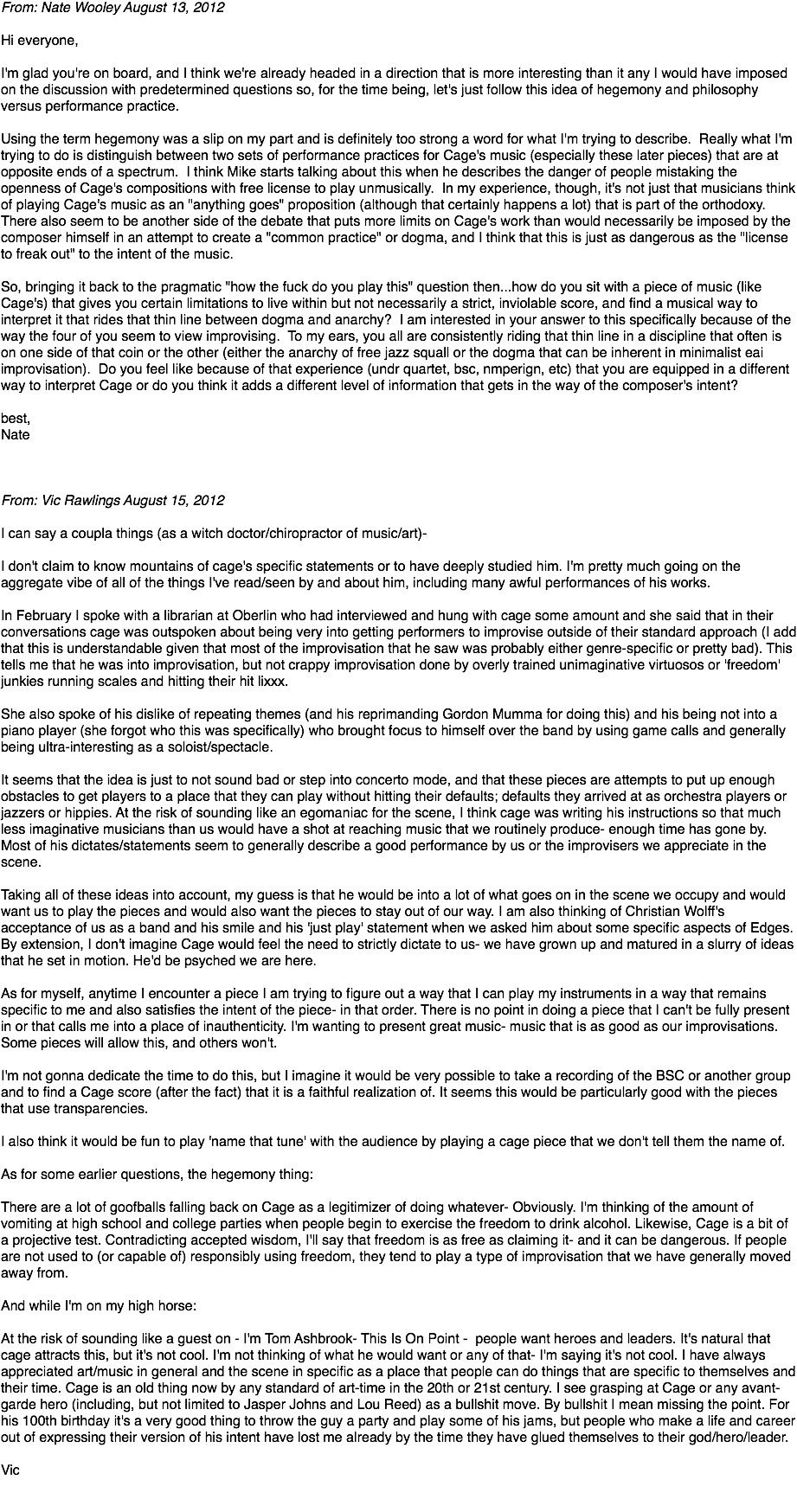

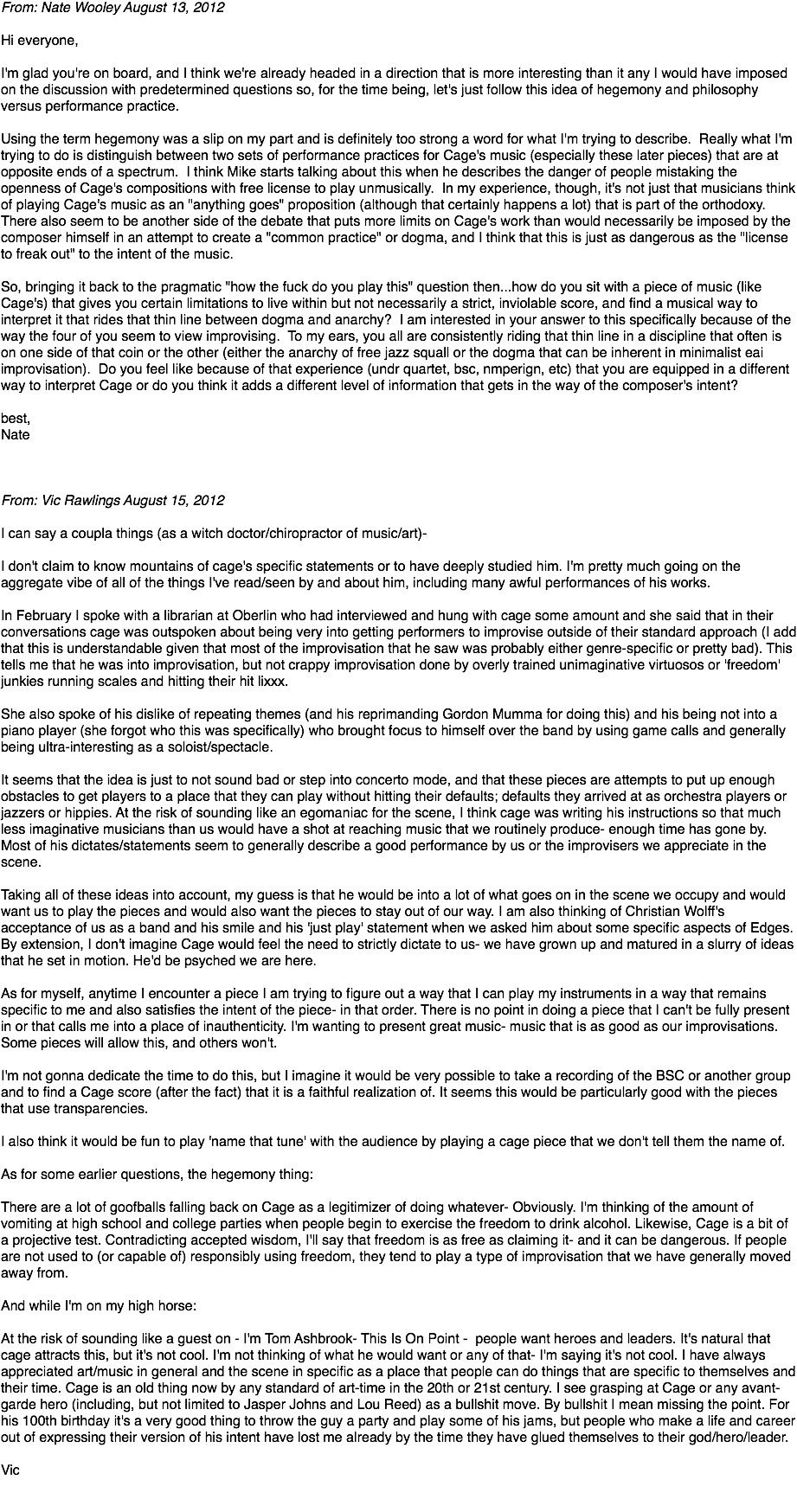

![From: Nate Wooley August 20, 2012 Hey everyone, There is a lot of information here (thanks Vic!) and I've read it now a couple of times. Since no one else has jumped in after Vic, I thought I would take the opportunity to give my impressions and then folks can go from there, or go back to the original question or into a different direction entirely. In Vic's email I latched on to a couple of things. Hegemony and hero worship aside (even though I think these would be interesting topics to follow up and am open to talking about them), if I concentrate specifically on how he's viewing the role of the BSC as performers of Cage and in a "tradition" of modern improvisation, a couple of questions come to mind. This may provide fodder for someone else to expound upon. 1. I'm interested in Vic's statement about the hierarchy of how, when he encounters a piece, he is: "trying to figure out a way that i can play my instruments in a way that remains specific to me and also satisfies the intent of the piece- in that order." In this statement, he’s basically saying that maintaining a very personal musical personality is first and foremost and the intent of the composer seems to come in a far second. Is this a common attitude among you as improvisers? To me, it seems counterintuitive to the basic notion of composition, but with a lot of improvisation language and aesthetic now coming from Helmut Lachenmann, Gerard Grisey, etc. I think a case could be made for this. 2. Let's say we agree with the above idea that, in this musical landscape with improvisers that are much more complex and savvy in the languages they work in the scores of Cage's later period might take on a different meaning than they did when they were being written. If Cage really would be willing to step back and allow you to "just play" (as Christian Wollf did) then performing his works now seems like his work would be nothing more than a group exercise more suited to a rehearsal and discussion amongst players than to a dedicated performance. What then, if anything, makes performing Cage's scores meaningful? Hope everyone is doing well, Nate From: Mike Bullock August 20, 2012 Hey folks, A lot to think about here: About Vic’s quote: "trying to figure out a way that I can play my instruments in a way that remains specific to me and also satisfies the intent of the piece- in that order." In that sense the interpretation of the piece becomes like a cooperation across a gulf of time, where you are kinda "collaborating" with Cage, which I think is a good pragmatic way to approach most indeterminate scores. Morton Feldman gave a nicely distilled version of that with his early scores where the performer is free to choose one element (e.g. pitch or rhythm or duration, but not all of them). There's a hoary old tradition of composers in the "western tradition" fearing or distrusting or even sabotaging their performers, and writing that into their music, e.g. Brian Ferneyhough composing absurdly complex rhythms because he wants the sound of people trying to play them but not quite succeeding. Though Cage is often cited as not liking improvisation, I think he definitely liked to collaborate with his performers. When improvising in an established ensemble, we are all collaborating with each other in a composerly way as well as a performerly way; in a sense, each performance by a long established group like the BSC is like a new iteration of a piece called "the BSC." Not that they all sound the same, but that's an interesting way of thinking about why groups get certain distinct sounds and a distinct level of comfort (not boredom). Vic, I must take exception to your idea that any given BSC piece could be matched to a Cage score after the fact - to me that's falling into the trap of saying that Cage = Everything, that he encompasses all possible sounds and sound-related actions. To the best of my knowledge he never wrote anything that leaves his own input out entirely (in spite of his stated intentions, perhaps). Though the "name that tune" idea is interesting - not that anyone is necessarily going to name the tune, but it would be interesting to hear the guesses of Cage-savvy listeners. And about Nate’s quote: “Maintaining a very personal musical personality is first and foremost and the intent of the composer seems to come in a far second. Is this a common attitude among you as improvisers?” Hard to say, since we don't play a lot of composers' stuff. I'm gonna guess Vic doesn't mean it as a priority thing - like I'm going to throw the score out the window if it starts to bum me out - but just in terms of a to-do list as an interpreter. E.g. never mind all the things that *can* be done with this piece, what makes sense for *me* to do with it? For me, I'm looking at these pieces trying to find an opportunity to do something authentic (eek, that word), that is something that "I would do" or has some kind of vibe with my own values and priorities as a performer, while also looking to be challenged a little by Cage to do something a little new, so I'm not just playing "my thing" and tacking Johnny's name on the end. For example, there's a lot of humor in these scores, some of it subtle, some of it obtuse; I used to do a lot of stuff in my solo work that involved use of theatrical or performative elements, and I took great pains to try to ride a fine line of subtle humor and awkwardness without being dramatic or clownish. So I might be interested in some of Cage's staging instructions, but not the cartoonish or political ones. I'm also not so interested in the pieces that involve, for example, reading Thoreau's face like a score; there was a time in history when doing that was revolutionary and liberating, but now I think that sort of thing is an excellent étude for a student improviser but not so interesting for an experienced one. Cage was not working with people who had already done hundreds of pages of graphic scores in their lives, with maybe some exceptions (Tudor). And, Nate’s other question: 2. Let's say we agree with the above idea that, in this musical landscape with improvisers that are much more complex and savvy in the languages they work in the scores of Cage's later period might take on a different meaning than they did when they were being written. If Cage really would be willing to step back and allow you to "just play" (as Christian Wollf did) then performing his works now seems like his work would be nothing more than a group exercise more suited to a rehearsal and discussion amongst players than to a dedicated performance. What then, if anything, makes performing Cage's scores meaningful? This gets the question of "Is Cage more useful as a philosopher than as a composer?" There are some people who feel this way, and it's understandable - I felt that way for a while when I first read about him. I don't feel that now. With Christian [Wolff], it may have been a situation where, nowadays, he has been playing with experienced improvisers for years at this point and he knew that we fit that category. Maybe he wanted to do that with us because it's a rare opportunity for him to do so at a Conservatory, where most of the students are working on his written pieces (and lucky to be able to wrap their heads around that). Even at New England Conservatory, one of the most forward-thinking conservatories going, anything beyond Mahler is still utterly alien to most of the students and teachers. In order to keep meaning in performing Cage scores, I think it's important to remember that it's not hard to sound like yourself in a Cage score; I feel he wasn't writing to try to get a certain sound out of people, but to set up certain structures and possibilities. -Mike From: Liz Tonne August 20, 2012 Phew! Well here goes..... Certainly, I was being facetious in joking that perhaps I was unknowingly a Cage-ist. I really know very little about John Cage, I have never read any of his writings and the only article I have read about him was in the Gastronomica journal in regard to his work on mushrooms. I suppose what I think I know about John Cage is from hearing other musicians, or people interested in music, or people who once knew him, talk about his work or about him as a person or what ever they think they know about John Cage. Other than that, I have performed 4 of his compositions, some of them more than once. I have also looked long and hard at all 92 of the songs in the Songbooks trying to figure out if and how I could possibly perform any of them. In this light my responses to these thoughts are completely subjective. One of the Cage pieces I have blissfully done a few times now is Ryoan-ji and I could talk about that piece forever because I absolutely love it. The other 3 have all been from the Songbooks, #52 & #53 (the Songbook Aria's) and #85. In the process of selecting pieces from the Songbooks, that I felt I could even begin to pull off, I tried to familiarize myself with a few of the indeterminate scores that could have set the context for the pieces. Because I am a vocalist, and purely out of curiosity, I have also looked at what I think of as Cage's Artsongs, purely notational compositions written for voice and accompaniment. What I have taken away from looking at these scores is that they are all COMPLETELY different and that there is no way to generalize about Cage's music or really have an informed discussion about John Cage's music without selecting which of his vast number of compositional styles and eras you are talking about. Even within the Songbooks themselves the diversity of approach is immense. They range from fluxus-like theatre pieces to traditionally notated scores. So, as improvisers perhaps we need to specify that we are talking about how John Cage composed to accommodate improvisation? But even here we are in a vast sea of many, many different improvisational systems. Many, I'd even begin to say most, of these seem highly specific - not much Free Jamm allowed. Let's say we agree with the above idea that, in this musical landscape with improvisors that are much more complex and savvy in the languages they work in the scores of Cage's later period might take on a different meaning than they did when they were being written. I definitely did not feel in the least bit savvy trying to sing the Arias - I carefully selected techniques which I felt I had developed for myself and applied them to the system detailed in the directions to the score. Basically, I was trying to make it workable for me with the tools which my personal experience has given me - and it was still very, very challenging. I found these to be serious compositions and I have gained a lot of respect for each and every one of them as a separate entity. "Is Cage more useful as a philosopher than as a composer?" No. For me, I'm looking at these pieces trying to find an opportunity to do something authentic (eek, that word), that is something that "I would do" or has some kind of vibe with my own values and priorities as a performer, while also looking to be challenged a little by Cage to do something a little new, so I'm not just playing "my thing" and tacking Johnny's name on the end. That pretty much sums it up for me too. I'm also not so interested in the pieces that involve, for example, reading Thoreau's face like a score; there was a time in history when doing that was revolutionary and liberating, but now I think that sort of thing is an excellent étude for a student improviser but not so interesting for an experienced one. Interesting point Mike - many of these don't readily lend themselves to personal expression, but they are compositions! They aren't meant to be about the performers - though some allow a lot of freedom to put yourself in there. (and some... Ryoan-ji.....are transcendent) Thankfully that is all I can think of to say right now. liz From: Mike Bullock August 21, 2012 This is great, Liz - coming from the one among us who has most likely played Cage the most. Re: your last comment relating to personal expression - last night in conversation with Linda and Vic and Liz W, I was reminded of a major revelation Cage had in his early career (when he was writing some of these art songs you are talking about, I think, like The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs). He was trying to pour a lot of himself into his pieces, and people were just "not getting it" and finally he had the revelation "music may be expression, but it's not self-expression." I thought that was a great way to sum up moving beyond the personal into the trans-personal, interdependent way of making music that is a lynchpin of improvised music. -Mike From: Bhob Rainey August 23, 2012 Hi, I'd like to take a step back and try to address some of the fundamental questions that Nate is putting forth and that always seem to be looming whenever an improviser from our generation performs an indeterminate score. Implying that contemporary improvisers have internalized and possibly improved upon both Cage-ean concepts and the instrumental language that arose around those concepts, Nate asks, "What then, if anything, makes performing Cage's scores meaningful?" Meanwhile, Vic postulates that, to a listener, an improvised performance could be indistinguishable from the performance of a Cage score. I think that the trouble expressed by both of you boils down to the question, "What constitutes a good performance of an indeterminate piece?", and, for the improviser / performer, "Where do I place my disciplined effort?" As to the first question, it's obvious but not always expressed that there is a significant shift in the score / performance relationship with indeterminacy. It is possible with a work by, say, Brahms, to derive the score from a given performance – just by listening you can figure out the notes, rhythms, dynamics, etc. So, the performance is a "realization" of the score, and the two resemble each other. The degree to which the performance resembles the score is a major criteria for judging the quality of the performance. This criteria is absent in indeterminacy, where a single score can produce radically different performances, none of which reveal with any kind of accuracy the score underlying them. In this case, the performance is an "actualization" of the score; there is no resemblance, but there is still an intimate link – the score provides the potentials and problematics necessary for the performance without specifying the outcome.* The lack of resemblance between performance and score in indeterminate music opens up a wide field for charlatanry – no one can tell if you're playing it "right" or not, so why not do whatever you want? Cage already supplied the answer: "Permission granted. But not to do whatever you want." Depending on your disposition, this is either a perfectly succinct summation of a fascinating worldview or it's a coy dodging of the question. Cage said a lot more than those nine words on the subject, and I believe he answered the questions of why an indeterminate score is significant and what constitutes a good performance of it rather thoroughly. The problem is that the answer feels less like an answer than an injunction: "Perform a disciplined action." Think of it like this: a score like Song Books is a framework for an event. "We are gathered here this evening for a performance of Song Books." Song Books is the reason for the gathering, and it provides a number of significant potentials for the direction of the evening. It opens up possibilities but also closes many others. It tells you what to do, but not so specifically that you forget the other parts of the sentence: "We are gathered here…" "We" are the performers, audience, animals, the things in the space of "here", which is both place and time. We are spending a certain duration living around Song Books, and our respect, our disciplined effort, is directed towards that ecosystem. It isn't "Song Books will be performed this evening" or "I'm playing Song Books tonight" or "This is what Song Books sounds like". A good performance of Song Books is a productive, ethical engagement with the score, the time, the place, and the life of the performance. You could say, "remove the 'score' part and you have improvisation". I would say that the "score" in improvisation (as we practice it) is an embodied, fluid history. It is always unfinished, almost impossible to prepare. The advantage of an indeterminate score is that you can know better what you are preparing and can proceed with the confidence that this preparation has been in some sense sanctioned by a thoughtful person (i.e., the composer). The freedom that emerges is really a freedom from your own taste (quite different from the freedom to do whatever you want), so that you might open up a space for beauty rather than fill a space with your ideas. Can you do the same thing with improvisation? Yes, but it's hard. You have a more direct conflict with your own history, your taste, and as soon as you feel that you've surpassed these things, they adapt. I love the self-splitting snags of this particular struggle, but these are not the only things I love about making music. I'm tired now. -bhob * And if you haven't read Joe Panzner's dissertation on Deleuze and Cage (to which I am somewhat indebted for my Deleuzian interpretation of the relationship between scores and performance), you're really missing out.](images/u10766-198.png)