Syntactical ghost trance Music: A Conversation

Kyoko Kitamura & Anne Rhodes

Anthony Braxton’s contemporary music is flexible with its scoring. A far cry from the orchestral and big band works of the 1970s and the chamber music of the 1980s, the modern output is defined, in large part, on its interchangeable instrumentation. One of the outcomes of this trend is his increased use of the voice in the last ten years.

Obviously, the Trillium cycle, so brilliantly expounded upon by Katherine Young in these pages, is dependent on text and the vocalists to bring Braxton’s characters to life and move the narrative forward in a linear fashion. They are responsible for story, philosophy, humor, and—in large part—for setting forth the very specific iconography contained within each opera.

But, like all the parts of the composer’s larger system, Syntactical GTM and its use of non-textual vocal sound finds its way into Pine Top Aerial Music and Falling River Music, and so the role of the voice becomes somewhat ambiguous outside of the operas, with only rare performances of a strictly Syntactical GTM piece.

To help elucidate how voice and the vocalist works within Braxton’s compositional system, Sound American began a discussion with two artists who have worked extensively with and within all aspects of Anthony Braxton’s music: Kyoko Kitamura and Anne Rhodes. Both vocalists have an extensive knowledge of the history of what the voice can do in and out of classical and jazz traditions and have developed a highly personal virtuosity that provides the perfect instrument for the composer’s experimentation in narrative, linguistics, and meaning. - Nate Wooley

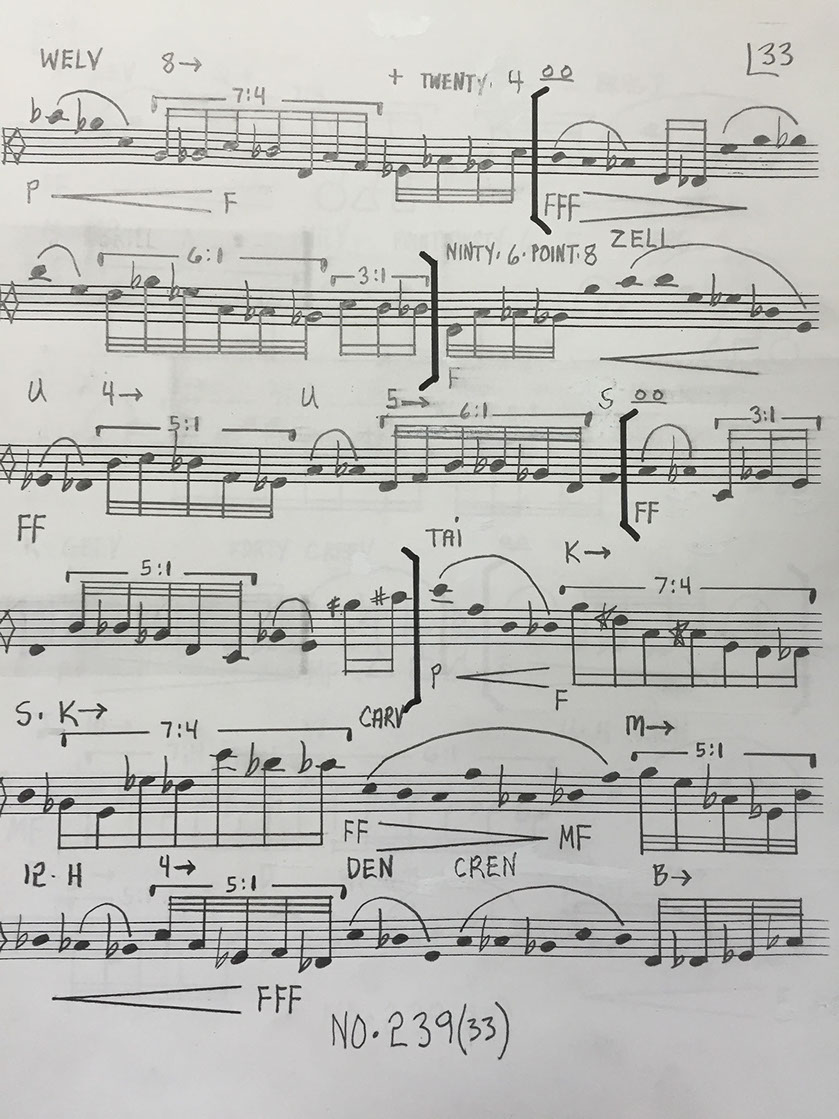

A Page from Composition 239 featuring elements of Anthony Braxton's Syntactical or voice-related scoring.

Sound American: I have two initial questions:

1) In your opinion, as two of the most consistent vocalists to work within Braxton's compositional system, what space do you think Syntactical GTM and the other vocal works occupy in the context of Language Music, GTM, Trillium (obviously), or some other context I may have overlooked? What do you think acts as a direct correlation to the instrumental and what do you think is specific about the vocal music, besides the obvious difference in instrumentation?

2) It seems that the language types constitute a sort of center or structure for much of his other compositional systems, and yet, Syntactical GTM and Trillium are the only two forms that specifically use spoken or sung language as part of their mechanics. As performers well versed in both systems, can you explain how the use of language differs between Syntactical GTM and the, perhaps more traditional, opera cycle?

Kyoko Kitamura: Before getting into the big picture of where vocal music occupies within AB's [Anthony Braxton's] world, I'd like to add my observation that there may be these categorizations possible regarding his vocal music:

1) Voice used as another instrument within the ensemble: Falling River Music, ZIM MUSIC (no specified difference marked by AB regarding the use of voice and instrument; voice improvises similarly).

2) Voice used with syllables that only a voice can make: Syntactical GTM (consonant/vowel combinations that only voices can make, marked by AB himself as part of the original written music; voice improvises similarly to an instrument within the system).

3) Voice used with actual words but not necessarily long-form narrative content: secondary material of Comp No. 192 (and maybe Anne knows more?) where specific words/sentences are specified by AB.

4) Voice used with narrative content aligned with AB's philosophy as expressed in his Tri-Axium Writings: opera, Comp No. 173 (and maybe Anne knows more?) where specific lyrics/libretto is specified by AB with very little improvisation written within the score itself.

All of the above seems to have slightly different places in AB's musical world. Maybe there are two overlapping questions here. One is the use of voice in AB's musical world, which encompasses performance practice for all vocalists performing any type of AB's composition regardless of whether the composition was written with vocals in mind. Then there's the composition aspect, where AB intentionally included voice-specific elements to be used by vocalists, whether it be consonant/vowel combinations or full libretto. Perhaps we can start with the latter, concentrating more on #2,3, and 4 first, as a starting point for answering Nate's question. (Later, I'd love to discuss the performance aspect of being a vocalist performing AB's music, and specifically around vocal improvisation, but Nate's first question seems more about the composition aspects of AB's music.)

Anne Rhodes: Language Music is by nature very open and flexible, and I wouldn't say that the voice occupies a separate space in that context. However, I think it's worth noting that Anthony conceived it with his own instruments (saxophones and other reeds) in mind. For other musicians, including vocalists, some of the language types—such as long sounds and gradient logics—transfer pretty directly. Others, though, manifest differently for other musicians, perhaps especially vocalists. I would say that overall those differences present more opportunities than challenges. For a vocalist, legato formings can easily be executed as a smooth glissando, and sub-identity formings can include words and lyrics. Multi-phonics pose something of a challenge. Before I learned overtone singing, I used to make guttural grunts in an attempt to emulate the sound of multi-phonics on the saxophone.

While Syntactical Ghost Trance Music (the name Anthony gives to those GTM pieces that have lyrics) is the only class of GTM that overtly uses the voice, vocalists can and have performed non-Syntactical GTM; these pieces just require the vocalist to get creative with sound—use initial consonants rather than glottal stops, vary vowel sounds, etc.—in order to avoid fatigue. At first, Syntactical GTM might seem simply to be GTM that is better suited to the vocal instrument: a sub-genre that expressly invites vocalists to participate. In fact, Syntactial GTM is significant not just at the nuts-and-bolts level, but in the greater context of the entire Braxton oeuvre. This first became clear to me with the formation of the Pine Top Aerial Music sextet. One of the things that happens in that ensemble is that, while three instrumentalists and two dancers move about the space while working primarily with Language Music and improvisation and wearing Falling River Music on their wrists, a single vocalist sings Syntactical GTM. The numbers and letters in the lyrics of the GTM can activate the other ensemble members to perform specific parts of their Falling River Music scores. It was a little stunning, after several years of performing Syntactical GTM, to discover that those letters and numbers are there for a reason. And it helped me realize that Anthony's music is full of details that can seem incidental in one context, and then in another context those same details can open up or connect to a whole other world.

Similarly, on a surface level the Trillium operas provide a platform for Anthony's narratives. But embedded within the libretto are phrases that can activate certain events within the piece. I can't get much more descriptive about that, because I have yet to perform in a fully staged version of one of the operas, so perhaps Kyoko can elaborate. I can say that each libretto is peppered with passages that take the character and listener outside of the narrative at hand and offer an elaborate philosophical idea (these passages usual begin with the "secret password" indicated at the beginning of the score). When I am learning a Trillium role, I highlight these parts in a different color to remind myself that perhaps I am no longer fully in character when they arise, but rather channeling something like an omnipotent entity. It's almost as if there is potentially a Greek chorus built into each character.

[Composition] 175, for two vocalists, orchestra, and constructed environment seems to use the voice solely as a vehicle for narrative. However, even though I've performed it myself, I wouldn't be surprised to find that the lyrics are more functional than I knew at the time. Another of Anthony's vocal pieces that I have performed is [Composition] 307, for soprano and orchestra. In that piece, the vocalist seems to channel Anthony himself. It has a dream-like quality, and long instrumental passages are interspersed with conversational phrases, many of which Anthony's friends and colleagues will find familiar. Again, it's entirely possible that these phrases may have the potential to provide some kind of information to other performers in some contexts.

I think all this is to say that Braxton really uses the voice in a multifaceted way. As with most aspects of his music, performers can get a lot of mileage from just performing one layer of a vocal piece (such as a Syntactical GTM used as a straight-ahead ensemble piece) and always have the potential to add other dimensions.

SA: There is one phrase that Kyoko uses that I think is very fascinating to meditate on when describing Syntactical GTM: "voice used with syllables that only a voice can make." Anne, you pick up the idea a little in your discussion of using the voice in Language Music as well. I wonder if we can explore the implications of what only the voice can bring to Anthony's music that no instrumentalist can: vocal-specific sounds (and what that means emotionally) and telling a story; both practices that carry a lot of overt humanity to a music that some may view as somewhat alien, or transcendent of base human response.

KK: Let me jump right into the recent Braxton operas, Trillium E and Trillium J, because it is easy to see that the role of the voice is very different from that of other instruments. The vocalists sing the libretto, written in English, which tells a story through words.

In order to "explore the implications of what only the voice can bring to Anthony's music" as Nate put it, I'd like to compare my experience working with Trillium E and Trillium J.

Trillium E was the first-ever studio recording of a Braxton opera. It was also the first Braxton experience for many musicians, myself included (and in my use of the term "musicians," I include vocalists, since I often do not know why "vocalists" seem to be separated from "musicians"). The focus, naturally, was on the music.

Trillium J, on the other hand, was a staged production as well a recording project. Many who were involved in Trillium E were also involved in Trillium J. Because of the requirements of staging an opera, all of us spent more time together. The sense of community was much stronger. The focus was not only on the music, although the music was definitely the priority, but also on all aspects of staging. Through hours of rehearsals and discussions, we dug into the three layers of the opera according to Anthony, which we did not explore to this extent in Trillium E:

1) Apparent universe (the surface layer of the story)

2) Secondary invisible universe

3) Esoteric universe

Without going too much into the details, as there is another section of the issue dedicated to Trillium J [Katherine Young's Writing on the Trillium Operas-Ed.], I'd like to say this. I feel that the voice's ability to form words, then sentences, and then tell a narrative, allows Braxton's multi-layered philosophical approach to be fully embodied in his music. Anne points this out in her previous reply when she says, "each libretto is peppered with passages that take the character and listener outside of the narrative at hand and offer an elaborate philosophical idea...It's almost as if there is potentially a Greek chorus built into each character." As Anthony himself says of the opera, "Nothing is as it appears." There are layers and layers of universes, in his music as well as in his philosophy. The voice allows this multi-layered characteristic to come out in the music, in a way that is unique to the ability of the voice.

At the same time, I feel it is important to note that this came about in Trillium J because the requirements of staging an opera put us into that zone where we could explore the multi-layered aspect of the work. It was the amount of time we spent together, that we had stage directors (Acushla Bastible and Louisa Proske) to whom Anthony would articulate his philosophy with us vocalists listening in, that we had a choreographer (Rachel Bernsen) so that we vocalists understood the composite aspect of the system connecting physical movements to the character/role in the opera, which finally led me to understand the polarity aspect of the opera, that what appears on the surface, like humor, has balancing force beneath it, which was on the other end of the spectrum.

Perhaps the opera, as a genre, is what makes all of the above happen. And, can there be an opera without the voice? I'm going to stop here because this is a lot of material, and I'd like Anne and Nate to be able to chime in, as well, of course, correct, if necessary. I do have other things in mind for Anthony's vocal works which is not long-form narrative.

AR: The obvious manifestation of "syllables only a voice can make" is, of course, language: opera libretti, the lyrics to other vocal pieces, and the numbers and letters in Syntactical GTM. But as Kyoko states, SGTM is also made up of non-linguistic syllables. I won't claim to know Anthony's full intentions for these, but on an aesthetic level, he takes advantage of the ability of the human voice to deftly create complex textures and timbres in a way that instruments cannot. When we speak, we use the vocal folds, throat, lips, tongue, soft palate, hard palate, airway, nasal cavity, larynx, pharynx, diaphragm, teeth...so many different body parts, without even thinking about it, to create a vast variety of sounds. In SGTM. Anthony leverages this ability by writing syllables as simple as "boo" and "nee" and complex as "yezve" and "shmv," each to be sung on a single beat. This is not only something only the voice can do, it also pushes the limits of the voice in an unusual way. But at the same time, it helps prevent vocal fatigue; a variety of sounds is much less taxing over the long haul than a single repeated sound.

Pine Top Aerial Music (PTAM) uses SGTM to create a backdrop for the improvising instrumentalists and dancers: a sonic space for the other performers to inhabit. While the other performers move around, the vocalist sits to the side. It's the closest situation to solo voice as accompaniment as I can think of. On a practical level, GTM as solo vocal music is (as I imagine it might be for instrumentalists) pretty challenging. You really have to set a realistic tempo for yourself and find ways to breathe that don't disrupt the pulse.

KK: One of the eye-opening moments about the opera for me actually came after the opera, when I started using excerpts of the opera as secondary and tertiary material in the Anthony Braxton Trio (AB, Taylor Ho Bynum, myself), first as improvising material for Falling River Music and then with ZIM MUSIC. I was able to experience firsthand Anthony's compositions continue to develop, alive as ever outside of its original context. (Note: As I understand it, once a Braxton composition is performed in its original state for the purpose of being recorded, and once the recording is in the can, that composition is said to have an “origin” recording after which it becomes ready to be incorporated into other compositions as "secondary" or "tertiary" material.)

Two reference points that helped me: One is tradition. In my case, I went back to Billie Holiday, Betty Carter, and Jeanne Lee. The way Billie Holiday understood the music so deeply that she was able to take such gorgeous liberties with the melody without diluting the music in any way. The way Jeanne Lee and Ran Blake took well-known standards into another space.

The other reference point came from watching how choreographer Rachel Bernsen translated Anthony's system into movement during the production of Trillium J and the Sonic Genome. I wondered then about choreographing a movement on earth, and then performing it outdoors on the moon. The difference in gravity, not to mention the lack of air, will make the dance into something completely different, but the core would still be the same. Could I do something like that, take the essence of a part of the opera and move it through different spaces? Which forced me to reexamine who I was as a vocalist and as a human being. Examine all the mannerisms I acquired over the years and strip them away. Find my essence, which can travel through different spaces. Dissect everything, study them, rebuild. The vowels, consonants, my register, the crescendos, and more. Which has affected me in everything I do, and especially in the way I currently approach the voice. I'm still working it all out (but an attempt can be heard in the Language Music section of the issue).