Ghost Trance Music

Erica Dicker

Event-Space

Many of us habitually turn to news media that bolster our own belief systems and affirm our world view. In times as complex as these, when I find myself shutting off the radio or closing my laptop, frustrated by “the news,” my thoughts turn to a particular memory of Anthony Braxton: boarding an international flight with him and noticing an enormous, seemingly divergent stack of printed news publications under his arm. Braxton intently leafed through this spectrum of monthlies, weeklies, dailies, glossies, and tabloids—everything from US Weekly to The Herald Tribune—for the duration of our flight. I am grateful for this memory. It very simply illustrates Braxton’s ethos: to perceive the human experience from every possible point of view. Braxton exemplifies a way of being in the world I aspire to achieve; the very effort of doing so orients my approach toward all music and lends me a greater understanding of his.

Braxton’s ability to identify intersections between various cultural, social, and artistic practices informs his compositional process, enabling him to write music that relies on and celebrates the creative agency of the performer. His musical systems supply architectural foundations for “event-spaces,” where all performers and “friendly experiencers”—what Braxton calls listeners—can take part and engage with one another. He achieves this by designing interactive performance strategies “that can be used for three-dimensional investigation or experience.”1 The intuitive decisions made by players operating within these parameters support Braxton in realizing the most fundamental aspect of his work: All his musical systems are designed to interconnect. What is most remarkable about this process is that the act of unifying Braxton’s entire compositional output is a communal one.

One of the most straightforward contexts in which to examine Braxton’s process of unification is the Ghost Trance Music series, a set of roughly 150 pieces written between 1995 and 2006. Ghost Trance Music (or GTM) describes compositions specifically designed to function as pathways between Braxton’s various musical systems. One can think of GTM as a musical super-highway — a META-ROAD2 — designed to put the player in the driver’s seat, drawing his or her intentions into the navigation of the performance, determining the structure of the performance itself.

At the heart of Braxton’s work is an emphasis on interpretation over execution, a feature designed to empower performers to trust their intuition. He achieves this balance through the provision of highly detailed parameters first defined in music written in the 1980s for his long-standing quartet featuring Marilyn Crispell, Mark Dresser, and Gerry Hemingway. In this context, Braxton conducted experiments using various collage techniques, particularly the synthesis of through-composed melodic lines and other written pieces, as well as areas of controlled improvisation.3 This afforded the ensemble opportunities to carve the structure of given performances while the musical material retained its integrity.4

To make the experience repeatable yet variable, Braxton devised graphic pieces called “pulse tracks”5 —scores that are “to be played concurrently with other compositions”6 (see Example 0). Dresser or Hemingway were typically given pulse track scores and would play them, while Crispell and Braxton played notated material or improvised.7 Pulse tracks, such as Composition No.108-B, are read by the musicians “fairly literally… [adhering] to the time lapses that were happening.”8 Hemingway would interpret these pulse track scores as either “velocity diagrams” or “dynamic diagrams.” Thanks to such notational devices, Crispell, Dresser, Hemmingway, and Braxton were able to depart from and return to particular compositions, “explore fresh kinds of improvisation and interplay,”9 and stay unified as an ensemble.

Braxton’s inspiration for GTM came through his study of Native American musics, particularly the traditions tied to a post-colonial ritual called the Ghost Dance. The Ghost Dance spread throughout Native American communities in the late 19th- and early 20th centuries as both a spiritual practice and a movement seeking social justice. Surviving members of various displaced Native American tribes would come together and perform transcendental circle-dances, or ghost dances, in which the living attempted to communicate with their deceased ancestors.10 These ceremonies often lasted hours or days and helped disparate tribes establish larger communities as well as preserve the customs remaining to them.

The Ghost Dance provided Braxton with a vital structural model and affirmed his own ideas regarding human interconnection and ritual practices. GTM emulates the ceremonial and social aspects of the Ghost Dance and serves two purposes. The first is transcendental: GTM parts the curtain between Braxton’s past and current work, unifying it in the same “time-space.” GTM is also an arena in which Braxton helps curate intuitive experiences for both performers and listeners.

Example 0: Pulse Track from Composition 108B

Tool Box

“Erecting a context… that’s what we’re doing with this erector set.” —A.B.

Ted Reichman posited a wonderful insight illuminating the importance of the performer’s intentions to Braxton’s music: “In Anthony’s music there is a third thing, a thing between composition and improvisation—the golden moment.” This “golden moment” represents what GTM aims to achieve—an “event-space”—a context in which the input of each constituent determines the scope and trajectory of the communal experience.

For me, GTM represents the functionality of music-making in a community. In the hope of expanding the Tri-Centric Community and creative community as a whole, the following “tool box” will contain definitions of certain symbols, terminology, and descriptions of features fundamental to Ghost Trance Music. Since GTM can be divided into four periods or “species,” I will outline the salient features of each period to contextualize the resources in the tool box and empower readers to use them. It is important to recognize that Anthony Braxton’s Tri-Centric Music System is continuously evolving and my observations illustrate only one segment of an infinite line.

Reading Anthony Braxton's Ghost Trance Music

The Primary Melody

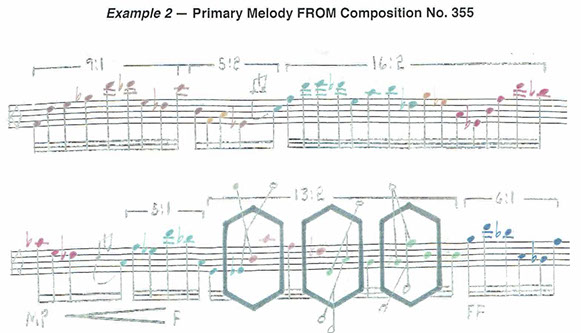

The Primary Melody is the most distinguishing feature of all Ghost Trance compositions (see Example 1) and consists of a single line of music, uninterrupted by any rests. Depending on the piece, these lines range in length from two to 80-or-more pages, evoking the footfalls of a ritual dance. Primary Melodies are designed to be read in unison by any number of musicians playing whatever instruments they can or choose to. Ranging from spare and simple, like the Primary Melody of Composition No. 199 (Example 1), to intimidatingly complex, like Composition No. 355 (see Example 2), this single line provides a performance platform in which any musician may participate.

Above: Example 1: Primary Melody from Composition No. 199

Below: Example 2: Primary Melody from Composition No. 355

Above: Example 3: Primary Melody from Composition No. 243

The Primary Melody is written in stemless eighth notes, occasionally with a circle, square, or triangle attached to them (see Example 3). Every piece of GTM contains these three symbols—visual cues suggesting points where the performer might decide to depart from (or return to) the ritual circle dance. Each shape corresponds to one of three aspects of Braxton’s Tri-Centric Model: the circle is abstract realization; the square is concrete realization; the triangle is intuitive realization. In the context of GTM, they indicate specific points where the performer is invited to depart from the score and read from secondary or tertiary materials, or engage in improvisation. These symbols can be thought of as portals or highway exits off the META-ROAD. Which adventure a performer takes depends upon the shape compelling them to move on.

Secondary Material — Triangle (Synthesis or Correspondence Logics)

The triangle is an invitation to move to another notated composition or “stable identity.” This implies a folio of one-page pieces called Secondary Material included at the end of each GTM score. Generally four in number, these pieces are “ritual logics” one can travel to upon encountering any triangles in the Primary Melody. Labeled by Roman numerals, Secondary compositions are invariably trios written in two systems. For the solo performer or a duo, any one of the three lines can be selected to play and switching between them is welcome. In a large group, the decision to play a particular line can be made before performance. In very large ensembles, choosing a line ad lib creates another welcome variable.

Tertiary Material — Square (Stable Logics)

The square is a pathway to pre-selected tertiary or “outside” materials. Prior to performance, these pieces are selected by the performer or performers and can be drawn from literally anything in Braxton’s oeuvre. For example, the tuba part from his opera Trillium E can be read alone by violin; the violin part in Composition No. 173 can be read by tuba. A piece of Falling River Music—a series of Braxton’s graphic scores—may be visited; a piece of the Echo Echo Mirror House Musics—scores combining cartography, evocative graphic notation, and Language Music symbols; Secondary Material from different pieces of GTM; any of his early opuses; or even another Primary Melody can serve as Tertiary Material.

Language Music and Improvisation — Circle (Mutable Logics)

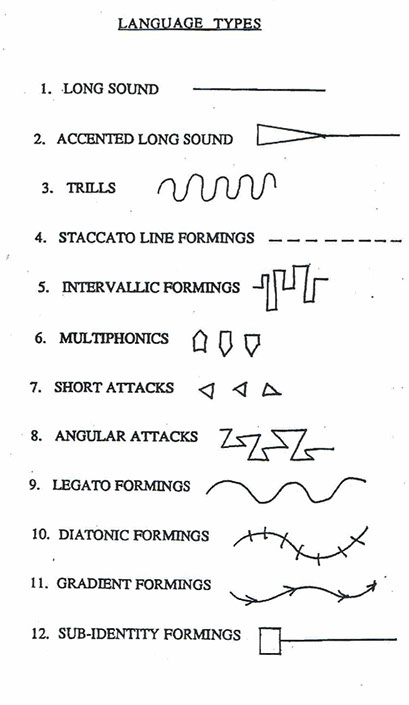

A circle is an invitation to engage in an open improvisation or a language music improvisation. An open improvisation is just that. A language music improvisation is based on 12 overarching language types (see Example 4).11 Players in the context of a large ensemble, like Braxton’s 12+1-tet, might conduct each other through these improvisations using gestures, indicating the number of each language type numbers with their fingers, generating a tremendously varied soundscape.

Open Clef

Many notational details are also foundational to this event-space. In all GTM there is only one clef; a diamond at the beginning of each staff. This “open” clef is interpreted in any clef or transposition, adding density to the Primary Melody as well as many “surprise” intervals to an ensemble performance. For example, a bassoonist or cellist might choose to read in tenor clef while their fellow bass-clef readers might decide to stay in their comfort zone. The decision to switch clefs is also a possibility—a rogue violist might suddenly transpose from alto to treble clef after leaving a repeated section or when moving to other materials. The variation produced by this simple device is one of the many techniques Braxton uses to ensure all performances of his work are unique.

“Rests”

A diagonal arrow often appears in many pieces of secondary material like those used in Composition No. 199 IV (see Example 5). This symbol can represent a rest, breath mark, or grand pause.12

Graphic Notation vs. Pitch

Secondary Material, though very pitch-oriented in early GTM, typically contains more graphic notation than the Primary Melody. These Language Music symbols and “imaginary logics” are catalogued in Braxton’s five volumes of Composition Notes. Though a thorough perusal of these notes is not necessary, familiarity with the 12 Language Types is essential.

Accidentals

Since GTM is written sans mesure, accidentals pertain only to the note next to which they are written. In addition to sharps and flats, Braxton applies “open accidentals” indicated by stars (see Example 6). These stars can be read as either a sharp or flat, at the performers discretion. In large ensembles, this generates variation by dissonance.

Example 4: Language Types

Above: Example 5: Diagonal Arrows as "rests" in Composition No. 199 (IV)

Below: Example 6: Stars as '"open accidentals" in Composition No. 181

Above: Example 7: "Brackets" in Composition No. 199

Below: Example 8: Syntactic Codes and Lyrics in Composition No. 341

Tempo

According to Braxton, “[all] tempos in this music state are relative.” The pulse is determined by the performer or performers who, in turn, are informed by the ways the secondary and tertiary music materializes.

Articulation and Vibrato

Articulation of the eighth-notes in the Primary Melody is to be short—unadorned —unless otherwise notated via a slurs or Language Music elements. The Primary Melody in all four species of GTM is, ideally, played non vibrato.13

Brackets

Sets of brackets delineate sections to be repeated at least once. In cases like Composition No. 199 (see Example 7), arrows point to certain brackets emphasizing that the material may be looped until the decision to move on is made. Material between brackets can also be isolated and used as a “stable identity” in performance.

Page Numbers

When performing music in an interconnected system, there is a distinct chance materials will be shuffled around. Braxton meticulously includes the number of the composition at the bottom of every page as well as the page number, twice—once at the bottom with the composition number and again at the top. In an ensemble, citing or signaling a specific page number is one way one player invites the others to move with them to other materials.

Syntactic GTM Codes & Lyrics

GTM, such as Composition No. 341 (see Example 8), sometimes contains lyrics consisting of syllables pronounced phonetically written above the staff. This “syntactic” GTM is designed to actively include singers in mixed ensembles. An exemplary recording of vocalists performing GTM is Syntactical GTM Choir (NYC) 2011, featuring a 13-member choir using GTM Composition No. 256 as the “primary territory of the performance.”14 In addition to lyrics, Braxton employs codes designed to engage singers and instrumentalists in interactive musical “play.” In the recording Composition No. 192 (For Two Musicians & Constructed Environment), featuring Braxton and vocalist Lauren Newton, the performers used a “wheel of fortune” spun to select particular codes. Any chance method may be employed when approaching syntactic GTM. Whoever casts the die, so to speak, then directs another performer or performers to the part of the piece whose number “comes up.” This “play” ultimately constructs environments with limitless parameters.

Use of Instructional System Notes

Ghost Trance Signals, as well was other details for navigating GTM, are contained in a valuable “cheat-sheet” called System Notes. Historically, System Notes served as an entry-level guide for participating in Braxton’s Large Ensemble classes, taught during his tenure at Wesleyan University.

Assembled from information contained in Braxton’s Composition Notes and other thematic diagrams, System Notes distills key concepts and provides abbreviated legends translating much of Braxton’s Language Music. They are a legacy of Braxton’s relationship with a dynamic string of teaching assistants at Wesleyan and continue to serve as a de facto reference guide. Parts of System Notes, or any notes, are typically kept on hand by performers, taped to stands, or near one’s feet. The most common tool to have on hand is a particular page containing the 12 Language Types (Example 4).

Tools in Hand: Ghost Trance Music in Practice

First Species Ghost Trance Music (1995–1998)

Comparing Examples 7 (GTM) and the more standard notation of Example 9 from Composition No. 103 for seven trumpets

First Species, Primary Melody

Steady Pulse

Looking at First Species GTM, it is easy to understand why many of Braxton’s collaborators and critics made great exclamations about GTM being a striking departure from his prior work. Examining Example 9, an excerpt from Composition No. 103, for seven trumpets (1983), we see what one might expect from an orchestral score: autonomous parts and the implication of a hierarchy between them.

A stark contrast is seen in Example 7 from Composition No. 199. Next to Composition No. 103, the absence of metric subdivision in No. 199 is striking. Evoking the steady beat of a single drum, it is fairly obvious that First Species GTM is ritual music.

No Specific Dynamics

Though there are crescendi and decrescendi written throughout the Primary Melody, there are no specific dynamic designations in First Species GTM.

Articulation

Apart from slurs, there is little articulation in First Species GTM—the notes that are not slurred are designed to be relatively short and incisive, like drum beats. Composition No. 181, which was the first piece of GTM, has no slurs at all. In Composition No. 199, Braxton gradually increases the number of slurred “passages” as the piece progresses while also increasing their length. In both cases, and in all First Species GTM, the steady stream of notes, all equal in value, is never obscured.

Few Invitations to Depart from the Page

In First Species GTM, there are typically no invitations to travel away from the primary material for at least the first page-and-a-half to two pages. It is my belief that Braxton “keeps it simple” in order for the Primary Melody to be clearly perceived as the beginning of a ritual.

Few Brackets

Compared to subsequent species of GTM, there are few brackets found in First Species. Brackets, like the Tri-centric shapes, rarely occur in the first page to two-and-a-half pages of material. I see this as another means by which Braxton emphasizes the ritual-music aspect of the work. Writing a Primary Melody that steps continuously forward, note-by-note, also challenges the performer to enter what Braxton might describe as a positive trance state.

First Species, Secondary Material

Secondary Material relies heavily upon graphic notation. A distinguishing characteristic of Secondary Material in First Species GTM is that much of the notation is also pitched (see Example 5).

Listen To An Example of First Species Primary Melody

Second Species Ghost Trance Music (1998–2001)

Example 10 Second Species Ghost Trance Music from Composition No. 243

Second Species, Primary Melody

Complicating the Primary Melody

Second Species GTM is often described as “the most musical” of the four, and, compared to first species, it is easy to understand why. In Composition No. 243, (see Example 10 above) Braxton exemplifies his use of “rhythmic breaks,” or subdivided beats, interrupting the steady stream of notes. Rhythmic breaks are divided into basic metic subdivisions (such as sixteenth notes, triplets, quintuplets, etc.—5:1 is favored in this example) and more complex polyrhythms (7:4 is especially favored, later in Composition No. 243). Infrequently, one might come across a polyrhythm in Second Species spelled a “fractional ‘tuplet.” An example of a fractional ‘tuplet would be 10 over two-and-one-eighth. Through fractional ‘tuplets do appear in a handful of Third Species compositions, they represent an experiment conducted, for the most part, at the end of the Second Species.

Dynamics

Another feature distinguishing Second Species GTM is the specification of dynamics throughout the Primary Melody. Ranging from mezzo-piano to fortissimo and including many subito indications, the dynamics in the Second Species give it much more shape and variation.

Articulation

Though Braxton writes ample dynamic contrasts in Second Species GTM, there are no articulations marked other than slurs.

More Invitations to Depart from the Page

Second Species GTM presents more invitations to travel to Secondary Materials, Tertiary Materials, and improvisations sooner than in the First Species and with greater frequency. It's as though Braxton perfected his means of highway construction and now has the confidence to engineer more exit ramps off of it.

Brackets

The potential for getting stuck along the same stretch of highway also presents itself thanks to an increase in the number of bracketed areas in the Primary Melody.

Second Species, Secondary Material

Taking the triangle “exit ramp” off the Primary Melody highway becomes a very different experience in Second Species GTM. Pitch relationships are not as important as the gestural dialogue and extreme dynamic contrasts (see Example 11 below). As in the case of the Primary Melody, these bracketed measures can be isolated and repeated as cells or read straight through.

Example 11 Gestural dialogue and contrasts of Second Species, Secondary Material from Composition No. 243 (I)

Listen To An Example of Second Species Primary Melody

Third Species Ghost Trance Music (2001-2004)

Third Species, Primary Melody

Obscuring the Primary Melody

What immediately distinguishes Third Species GTM from its predecessors is that the Primary Melody is generally “hidden.” Though you can still catch little glimpses of its spine, the Primary Melody has much more rhythmic meat on its bones. Braxton employs a wider variety of polyrhythms with greater frequency. In Composition No. 289, the “rhythmic breaks” are nearly continuous, interrupted only by small groups of eighth-notes. Certain works in this period also exhibit syncopated rhythms, grace notes, and, in a several few-and-far-between cases, fractional ‘tuplets.

Dynamics

Another distinguishing characteristic of Third Species GTM is its broader dynamic spectrum, ranging from quadruple pianissimo to triple forte.

Articulation

Third Species GTM, which begins with Composition No. 277, features accents as well as staccato markings that appear consistently throughout this period.

Invitations to Depart from the Page - Imaginary Logics

Perhaps the most interesting innovation Braxton brings to Third Species GTM is the incorporation of graphic notation from the Language Music catalogue. These events are referred to as “imaginary logics” (see Example 12 below) and present opportunities to treat notated material with the textures and extended techniques. This increases the number of road signs musicians see along the Primary Melody highway. Incidentally, this use of graphic notation anticipates the way imaginary logics will become an important part of Fourth Species GTM.

Brackets

Brackets are suddenly absent from the Primary Melodies of Third Species GTM.

Third Species, Secondary Material

Brackets are, however, still a vital part of Third Species Secondary Material. A more consistent blend of notated material and imaginary logics from Composition Notes are also a signifying attribute of this specie’s Secondary Material.

Example 12 "Imaginary logics" from Composition No. 388

Listen To An Example of Third Species Primary Melody

(Fourth Species) Accelerator Class Ghost Trance Music (2004–2006)

Example 13 Accelerator Class GTM from Composition No. 340

Primary Melody

Transcendent Primary Melody

Fourth Species GTM, also called Accelerator or Accelerator Class GTM, is a labyrinth of hyper-notated activities. Each beat is either subdivided or completely obscured by irregular polyrhythms. In an example from Composition No. 340 (see Example 13 above) the only un-subdivided beats occur beneath imaginary logics. Accelerator compositions exhibit a stunning gradient flow, “[giving] the “accelerator” melodies their characteristic feeling of constantly speeding up and then stopping to catch their breath.”15 Braxton also supplies generous grace notes and ornaments, destabilizing even the most basic polyrhythms.

Certainly intimidating in a large ensemble, these complex polyrhythms represent Braxton’s interesting relationship with rhythm. The function of these “rhythmic breaks” is, very literally, symbolic. Therefore, in practice, the performer is expected to target downbeats.16

Dynamics

The dynamic contrasts in Fourth Species GTM are much more extreme. Braxton marks subito dynamics more frequently and there is little middle ground between extremely soft and extremely loud.

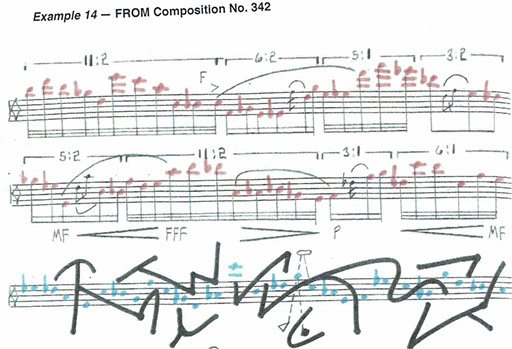

Articulation

Articulation markings are used sparingly but exactingly and vary from composition to composition. For example, in most of Composition No. 342, Braxton only uses accents at the beginning of slurs and only places staccato marks over pairs of sixteenth notes.

Color-coding

Articulation aside, Accelerator GTM becomes literally more “colorful.” Braxton color codes these compositions (see Example 14 below), providing them with another variable element and the potential for more dynamic and textural nuance. Each Accelerator Class piece comes equipped with a key defining the functions of the different colors that are applied to either pitched material (see Example 15 below) or imaginary logics (Example 13). In Example 14, from Composition No. 342, the color scheme is imposed directly over the pitched material.

Accelerator Whip

Braxton employs greater quantities of highly complex imaginary logics in compositions numbered 350 through 360. These ten pieces are their own subspecies of Accelerator Whip compositions, containing imaginary logics called “freeze frames,” (see Example 2) “where the musicians have [the] option of simply playing through in regular time, or dropping out and improvising [the graphic notation].”17 In other words, the performer may take yet another detour off the Primary Melody highway should they wish.

Accelerator Class, Secondary Material

Interestingly, there is no pitched material in the Secondary Material of Fourth Species GTM (see Example 16 below). The colors included in the key of each Fourth Species Primary Melody could serve the Secondary Material as well, however the colors rarely correspond completely. In Example 16 there are shades of green and yellow that are not depicted in the legend. This is an implication that Secondary Material can be interchanged. Apart from color coding, Secondary Material throughout the GTM series evolves little, remaining the most “stable” feature of this system.

Few Invitations to Depart from the Page

Braxton neither extends invitations to travel away from the Primary Melody in Fourth Species GTM, nor does he “bracket” any sections to be repeated. Its almost as if Braxton wishes to relish what he has so meticulously noted… And it may also be that the graphically notated and color-coded materials in Accelerator GTM supply enough detours to be taken off the META-ROAD.

Listen To An Example of Accelerator Class

Primary Melody

Above: Example 14 Color Coding in Accelerator Class GTM from Composition No. 342

Below: Example 15 Color Legend for Accelerator Class GTM from Composition No. 342

Below: Example 16 Secondary Material for Accelerator Class GTM from Composition No. 342 (IV)

About the Author

Violinist Erica Dicker works in a wide variety of musical settings, bridging the realms of orchestral performance and experimental improvisation. Erica is a founding member of the contemporary chamber music collective Till By Turning, violinist in Katherine Young's Pretty Monsters, as well as Vaster Than Empires, an electro-acoustic collaboration with composer and sound artist Paul Schuette and percussionist Allen Otte. She has premiered works by many composers including pieces for solo violin written for her by Olivia Block, Turkar Gasimzada, Ryan Ingebritsen, and Katherine Young. Erica also writes and performs her own music, exploring the idiomatic modalities and textures of her instrument.

Erica contributes her talents to various orchestras across the United States, including the Grand Rapids Symphony, and serves as concertmaster of the Tri-Centric Orchestra, an ensemble initially founded to premiere and record the operas of Anthony Braxton. Erica has also performed with Braxton’s Falling River Quartet and Diamond Curtain Wall Quartet at festivals in Belgium, Germany, Italy, Macedonia, Poland, and Turkey and appeared with the 12+1-tet at the 2012 Venice Biennale.

Erica earned degrees from the Oberlin Conservatory of Music (BM), the University of Minnesota (MM), and the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music (DMA). Her primary teachers include Gabriel Pegis, Marilyn McDonald, and Jorja Fleezanis.

Footnotes

1 Anthony Braxton, liner notes to Six Compositions (GTM) 2001, performed by Anthony Braxton and others, Rastascan Records BRD 050, 2001

2 This is a term coined by Braxton biographer Graham Lock and used throughout Lock’s work, particularly his seminal Forces in Motion, published by De Capo Press in 1988.

3 “[He] began to distribute parts of different compositions to the quartet members, encouraging them to insert materials from other compositions into the work as it was performed.” Stuart Broomer, “Braxton, Anthony,” jazz.com, accessed March 18, 2014, http://www.jazz.com/encyclopedia/braxton-anthony.

4 Ibid.

5 Lock, Graham (2008). “What I Call a Sound”: Anthony Braxton’s Synaesthetic Ideal and Notations for Improvisers. Retrieved from http://www.criticalimprov.com/article/view/462/992

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Alice Beck Kehoe, The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization, 2nd ed. (Long Grove, Ill.: Waveland Press, 2006), 7-8.

11 Braxton’s visual catalogue of sound. These pictorial classifications, called Language Types, “focus improvisations on particular elements [and] may be combined with each other,” and can be used like sonic building blocks from which to construct an improvisation. [Fei, James (2000, November 12). Anthony Braxton-Composition 247. Retrieved from http://www.jamesfei.com/247.html]

12 When I first played GTM, I completely misinterpreted this as some kind of glissando or graphic instruction to shift registers. I now stand gently corrected. But therein lies the beauty of Braxton’s work—he values intention above all else.

13 This has always presented a challenge for me as a “classically trained” string player, particularly when the rhythmic and registeral parameters expand in later GTM.

14 “Syntactical Ghost Trance Choir (NYC) 2011,” Tricentric Foundation, accessed April 15, 2016, http://tricentricfoundation.org/syntactical-gtm-choir-nyc-2011.

15 Ibid.

16 No one will be kicked off stage for failing to calculate their subdivisions with mathematical precision. The point is to try… and see what it leads to!

17 Bynum, Taylor Ho. (2014). About Anthony Braxton. Retrieved from http://tricentricfoundation.org/musical-systems